If you are one of the 135 million people [1] who have contacted Congress by letter, phone call, or online petition in the last few years, you've probably asked yourself: "Did that matter?"

Despite how good your civic action may have made you feel, the overwhelming odds are that your deed was essentially pointless - and, surprisingly, Congress is not to blame.

No matter who wins at the ballot box in the next seven days, we all lose for the next few years if we don't start solving this Tragedy of Advocacy.

**

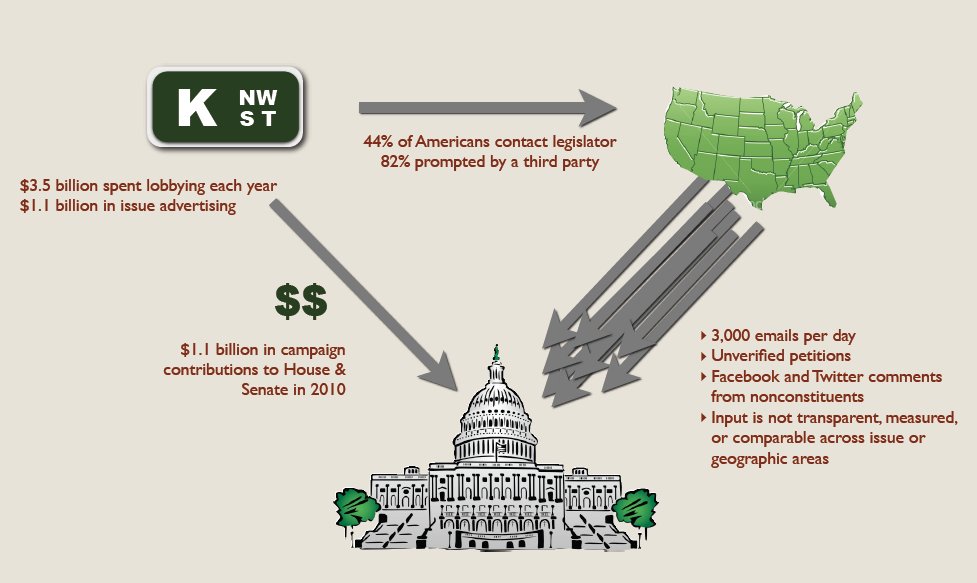

Lobbying Congress in the United States is a $3.5 billion dollar industry annually [2], with an additional $1.1 billion spent on issue advertising [3]. While large, those billions don't even include the budgets of the myriad nonprofits, vendors and other groups whose mission it is to drive citizen advocacy toward Congress. At the end of the day, it's impossible to know exactly how big, but added together, the industry is massive, and one of the biggest tools of the advocacy industry is mobilizing the grassroots - or asking people like you and me to "make our voices heard" by telling our representatives how to think or vote on an issue like health care or climate legislation.

Many of these advocacy groups have become incredibly savvy at enticing us to "share" or "act" with Congress online, employing professional staff that do nothing but try to get us involved. I know because I've been one of them for years.

Ultimately about 82% of all citizen action in the United States is generated through these teams at third-party organizations such as the AARP, Greenpeace or Focus on the Family, producing anywhere from 300 to 2,000 email messages delivered to each Congressional office every day - not to mention the barrage of Tweets, Facebook posts and other messages. [4]

Unfortunately, the very technology that has allowed virtually any citizen to share a message with their representative has also produced paralyzing noise, making Congress far less able to hear what citizens have to say.

The modern Tragedy of Advocacy is that all this increased share-your-voice-i-ness of citizens with Congress has actually resulted in more reliance on specialists and less on constituents than ever before. Congressional staffs often need those specialists (typically the dreaded "lobbyists" we love to hate) simply to distinguish signal from noise.

What's most tragic is that 91% [5] of those who contact Congress over the Internet do so because they "care deeply" about an issue. I know that's been true for me, and it's heartbreaking to think of how useless that expression of care has become on Capitol Hill. When that genuine concern meets a broken advocacy system, the frequent result is frustration. And frustration leads to apathy - the cancer of democracy.

Much has been written of late about "clicktivism," and whether the "loose ties" of online engagement can be compared with "movements" of the past. While there is merit in the rich, introspective discussion, both sides are missing a key point: the biggest problem isn't the connectivity of citizens to each other, it's in the last mile of turning millions of new citizen "voices" into anything Capitol Hill can actually use.

People are connected and engaged -- online and off. They are sending more letters, making more calls, donating more money, and attending meet-ups and house parties. But the messages they are sending to people who make policy are simply not getting through.

There are at least three reasons why this breakdown has occurred (read: there are others as well), and it's time to talk about them openly so we can fix them. I hope it's a conversation the responsible parties are willing to have...

1) Advocacy organizations (and funders) are disconnected from the realities of the political process on Capitol Hill.

Unbeknownst to most, advocacy organizations are in a constant and fierce battle for their most precious commodity: relevance.

Relevance for an advocacy group leads to influence, and influence leads to funding so that it can conduct more advocacy. This constant struggle also means that it's likely an advocacy group will ask you to sign meaningless petitions for the appearance of relevance. Your name, email address and zip code, after all, are the gold currency of the relevance ...err... advocacy industry.

(If you have doubts, sit around a Dupont Circle coffee shop in Washington, D.C. for half an hour until two campaigners sit down near you and have a conversation about "the size of their lists.")

It doesn't matter to most organizations that the petition you just signed to demand equal rights for Martians has absolutely zero chance of going anywhere in Congress; it's worth it to the organization to run the campaign anyway - particularly if a foundation or donor has given the organization a large sum of money to do so.

Further, if we judge by the "asks" of issue campaigns, then many (most?) advocacy groups don't actually understand what Congress can and can't do. Unless your petition, phone call or email to Congress is for or against a specific bill - and even more specifically: unless you're in the district of a valuable vote or committee chair for that bill - then your congressperson really can't do much for you at all. Your email or tweet saying you are "concerned about education" just adds your name to an education-focused organization's list or is ignored by Hill staff.

I personally have asked thousands upon thousands of people to write Congress in demanding things like a "clean energy future." There's definitely something to be said about symbolic efforts that gain media attention and that ultimately lead to getting a bill dropped in Congress, but, honestly, bills almost never actually get dropped for that reason. The two things any of Member of Congress can do are co-sponsor an existing bill or vote yes or no on it. Broad-based citizen advocacy should ask for one of those things. About the best response one can expect from Capitol Hill for a "demand" such as many of those that I've sent is to get a "well, that's nice." And I know because, if you read between the lines, that's more or less the response I've gotten.

Research from the Congressional Management Foundation shows that the constituents most pleased with their response from legislators were those who requested help with a specific problem. [6] Even though these requests require increased staff time and personal attention, individuals reported greater success here. Anecdotally, this supports the notion that Congressional offices really do want to be responsive -- they just need to receive a request that they are actually capable of fulfilling.

2) The systems designed to allow for citizen input are both not getting through to Congress, and creating more of the problem when they ARE getting through.

The software vendors who make the online tools allowing advocacy organizations to mobilize the grassroots know that email list-building is a critical metric, and as such, the tools are extremely good at building email lists. But they are very bad at delivering your message to Congress.

One of the co-founders of one of the most widely used tools for online advocacy once told me that the way they got around their "send an email to your representative" tool not actually sending emails to useful inboxes on Capitol Hill, was to turn emails into faxes and have the emails come out of Congressional fax machines.

That would be a kind-of-innovative solution except, if you ask a staffer on Capitol Hill about it (off the record) they will tell you, "Oh my god, don't send us faxes. We just throw them away."

In addition to the difficulty Congressional offices have in processing the deluge of incoming messages, the dirty little secret of the advocacy industry is that there are countless more advocacy emails from constituents that never even make it to Capitol Hill at all because of deep flaws in the systems that deliver them.

Estimates range widely, but rough ones from the professionals that have run these backend systems suggest that upwards of 60% or more of the emails sent never make it to the appropriate Congressional inboxes. That's right: well over half never make it through the proverbial door. Honestly though, no one really knows.

The folks that have built and run these tools (very good and caring people, mind you - many of whom I like very much) don't have much interest in sharing their petition/email-delivery effectiveness, because they are running businesses. But you can test it for yourself.

Find a petition that is supposed to deliver your message to your representative. Sign it, and wait a day or two; give the petition time to make its way through the system. Then call your representative's office and ask if they got it. Ask them to do a search of the emails they've received or check their faxes. Ask if they've recorded your input on the bill you commented on.

If your representative's office actually receives your message, please call me and tell me of your extraordinary victory.

3) Congress simply can't measure, make sense of, or act on what it gets from citizens.

Capitol Hill is full of good and caring people - as hard as that is for many outside the Beltway to believe. Ask Congressional staff members why they do what they do, and the vast majority will tell you, honestly, that they want to make a positive difference for their state or community. But, as already outlined, the sheer volume of incoming messaging is more than the minimal staff in each Congressional office can possibly handle - no matter how good their intentions.

Beyond volume, staff then have the issue of determining whether anything they're getting is actually from a constituent or not.

One of the best synopses I've seen of Congressional offices' ability to handle constituent concerns is this bit from Clay Johnson on the blog Infovegan.com:

Let's look at the math behind our representation: A member of the House of Representatives employs an average of 14 members of staff. On average, they have between 2 and five members of staff whose job it is to actually listen to constituents. It's a lowly job-- they get paid about 25,000/year, which in DC isn't even a living wage. So let's say that a liberal estimate for the number of people whose job it is to listen to America in the House of Representatives is 2,610. With a population of 307,006,550 people in the United States, that means there are about 118,000 people per pair of ears on the Hill.

Let's (unfairly) compare Congress to Comcast. Comcast has 23,000,000 cable subscribers. While I cannot find a total count of its customer service representatives, this article gives us a good idea of Comcast's ratio: three call centers in Washington State employ 1000 customer service representatives for 1.2 million customers. That's a ratio of 1200:1 for 24x7 service from what's arguably the corporation with the worst customer satisfaction in America, and its ratio is 10x better than that of Congress. While a better comparison would involve call volume of both entities, that probably explains why people are so dissatisfied with Congress. Noise levels have gotten so high that all Congress can listen to are Lobbyists.

It's remarkable that Congress is able to hear from the 307 million of us at all. In 1913, When Public Law 62-5 -- the law that mandated that the number of representatives had to stick at 435 -- went into effect, the population of the United States was just over 90 million people. That meant the ratio of Representatives to citizens was about 200,000 -- now it sits at over 700,000. While inventions in the media (like the television, telephone and email) have made it easier to communicate with the masses, a tripling of population gives our Congress more than it can handle on its own.

So the question once again becomes, how on earth do we start to fix these seemingly-intractable-and-only-worsening problems?

I certainly do not claim to have all the answers. I'm not sure anyone does. But I do hope we have the conversation, and here are a few ideas to start:

- Advocacy groups can commit to hand deliver all petitions to Congressional offices after they are solicited online (a handful of great organizers like my friend Adam Green do this, and it's about the only time petitions have an effect).

- As a citizen signing a petition, don't sign it unless there's a commitment from the organization asking for your signature to do a delivery. As an example, one particularly good delivery that I was proud of was this bi-partisan meeting with Rep. Brian Baird (D-WA) and Rep. John Culberson (R-TX).

- When it comes to online work, design a system from the viewpoint of Congressional staffers (This, surprisingly, has not been done before - at least not well), allowing advocacy groups to turn their members' voices into geographically measurable support or opposition to specific legislation in a way that Congressional staffers can make sense of themselves.

- Make advocacy public - and thus more transparent and accountable - by asking constituents to weigh in on specific legislation on an open system. Place measured and verified constituent input for or against a piece of legislation online, alongside the advocacy groups that have declared their position - eliminating non-transparent statements like, "we have 43,000 people in your district, Congressman" with no proof.

- At the end of the day, campaigners can simply ask themselves before they ask their supporters, "do we want Congress be able to make use of the input of our constituents that they're receiving or not?" If so, be clear in your ask about whether this is a membership or list-building activity or something intended for Congress. And be clear about what the best tool is to get a message to Congress - which almost certainly isn't sending them email.

Looking at the myriad new startups and apps out there, the good news is there's at least one new group seeking to tackle the taboos of advocacy head on - with real Capitol Hill experience and backing from Silicon Valley.

POPVOX, led by former congressional staffer Marci Harris, former lobbyist Rachna Choudry, and Govtrack.us creator Josh Tauberer, has tremendous promise. Give what they're building a look and let them know what you think - the only way it will help anything is if folks like us make use of it. If you write and give them feedback, your "voice-i-ness" is guaranteed to get through their system and be counted.

I should note, in full disclosure, that I've been working with POPVOX through their startup phase. I did not write this on their behalf, though I am greatly encouraged by their efforts. I got involved with POPVOX because this is an issue I am passionate about helping to overcome - having seen it from the inside - and felt it's time we did something about it. It's also the first time I've been outside the bounds of an organization, allowing me to be open and honest about my observations.

For fellow campaigners, I hope by starting the conversation outside of small sessions at bar camps (which we've had), we can be better. I don't think we should never use online petitions or sign ups, especially when trying to build community and long-term support for a cause - but let's be clear to supporters when community is our goal and when real political muscle is the goal.

If there's anything that I never want to hear again, it's this statement from a young man I met last week: "...I felt so good after I weighed in and signed that petition. I had no idea it was just going to get me bombarded with fundraising requests."

_________________________________

[1] How the Internet Has Changed Citizen Engagement, Congressional Management Foundation, ISBN: 1-930473-95-8, 2008, p. 2.

[2] Federal Lobbying Climbs in 2009 as Lawmakers Execute Aggressive Congressional Agenda, Center for Responsive Politics, OpenSecrets.org, February 12, 2010.

[3] The Endless Campaign, Report by Borell Associates, February 2010.

[4] How the Internet Has Changed Citizen Engagement, Congressional Management Foundation, ISBN: 1-930473-95-8, 2008

[5] How the Internet Has Changed Citizen Engagement, Congressional Management Foundation, ISBN: 1-930473-95-8, 2008, p. 17.

[6] How the Internet Has Changed Citizen Engagement, Congressional Management Foundation, ISBN: 1-930473-95-8, 2008, p. 28.

Follow Jake Brewer on Twitter: www.twitter.com/jakebrewer