In history, everything changes. The foundations of capitalism were built by merchants and mercantilists in the 16th and 17th centuries in response to the oppressiveness of feudalism. It developed into full-fledged industrial capitalism in the 18th and 19th centuries, and into financial capitalism at the end of the 20th century, using global free trade, shadow banking and offshore tax havens to overpower and sidestep much government taxation, regulation and control.

During the past five centuries, powered by the phenomenal stored energy of fossil fuels, the genius of free market capitalism has enabled the most incredible transformation the world has ever seen, lifting billions out of hunger and poverty, advancing science and engineering to incredible achievements, and enabling parallel social advances in literacy, education, health care, welfare, civil rights, communications and democracy. Its human and environmental costs have been huge, but we should not deny it its achievements. We are all the beneficiaries of its success, whether through health-care advances, digital technologies or the development of global consciousness thanks to the ease of travel.

Today, capitalism may appear stronger than ever, but its strength is increasingly delusional. It almost collapsed in 2008, and was only revived by a massive infusion of public money. Its financial foundations are deeply cracked, with trillions being staked on high-risk financial derivatives few can understand, and its social license is rapidly evaporating. A popular revolt is brewing, fed by three factors:

- Deep resentment at the accumulation of untold wealth in the hands of tax-avoiding corporations and elites while the majority of humanity struggles, and while communities and individuals all around the world suffer pollution and contamination as a result of capitalistic activity;

- The increasing indebtedness of state and national governments due to tax evasion and corporate influence over tax regimes, resulting in painful ‘austerity’ cuts to welfare, healthcare, education and other essential services;

- The well-referenced reality that global free market capitalism is driving global civilization towards the cliffs of climate and ecological collapse, threatening disaster to humanity and the species we share the planet with.

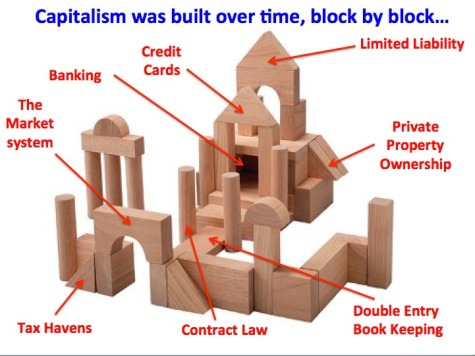

In response, a new green, entrepreneurial, co-operative economy is arising. Capitalism may appear to be a complex integrated system, but it was built over time, block-by-block and law-by-law by individuals and teams of people. The same is true of the new economy: it is being built block-by-block and law-by-law.

We do not have centuries to play with, however, as the founders of capitalism did. The need to prevent ecological and climate collapse is so urgent that if we are to stop the rising global temperature from blowing through the 2°C mark we need to reduce our carbon pollution by 10% a year—far faster anything being considered in global climate negotiations.

The need for urgent, rapid change challenges the core assumptions of modern free market capitalism and calls for the articulation of a clear alternative in the form of a green, entrepreneurial, cooperative economy that is able to generate the businesses and provide the work people need. For every ‘NO’ spoken in response the current economic model, with its increasingly risky and controversial fossil fuel extraction projects, we need to be able to articulate twenty positive ‘YES’es which show how a new economy can be built that is:

- Green, because it needs to operate on 100% renewable energy, and because all of its businesses will need to learn how to operate in harmony with nature;

- Entrepreneurial, because business of one kind or another will still be at the heart of the new economy, and successful business requires an entrepreneurial sprit and skills, however it is owned or managed; and

- Cooperative, because we achieve far more when we cooperate and organize to help each other in a spirit of kindness and mutual gain than we do in an Ayn Rand neo-liberal world of selfishness and private greed.

In our favour, we have communications so rapid that new practices and ideas can spread at a speed undreamt of in the days of Adam Smith. If we succeed, a historian forty years hence will be able to analyze how the foundations of the new economy were laid in four distinct realms:

- Personal values, attitudes and behaviors

- Local, regional and state economies

- National economies

- The global economy

This paper addresses only local, regional and state economies, for which I have identified an incomplete list of sixteen building blocks of change, some of which can be initiated independent of government, some of which require government leadership and action.

A truly successful economy must satisfy five fundamental human needs:

- The individual need to look after yourself and your family and make something of your life;

- The human need to care for each other and be to cared for in a spirit of community;

- The transcendent need to fulfill a vision and yearn for something greater;

- The practical need for good governance to keep our selfish impulses under control; and

- The ecological need to live in harmony with Nature so that we don’t undermine the foundations of our existence.

Today’s free market capitalist economy meets needs (1) and (3) with a reluctant acceptance of (4), while ignoring (2) and (5). A state-controlled fully socialist economy meets needs (2) and (4) while ignoring (1), (3) and (5). By meeting all five needs, a new green, entrepreneurial, cooperative economy can be more successful than the capitalist model, not less, where ‘success’ balances social and ecological prosperity and individual happiness with simple financial success.

These are the sixteen building blocks that this paper offers:

1. A Regional Business Network

In northern Italy, the Emilia-Romagna region is south of Venice, centered on Bologna. The region has a history of local cooperatives going back to the 1850s. Following World War II they built a robust economy under consistently left wing governments, with about 10% of their wealth coming from cooperatives. In Emilia-Romagna today private businesses work cooperatively to support each other, and in doing so they have created Italy’s most successful regional economy with the lowest rate of unemployment. There are half a million businesses and co-ops in the region, which pay a levy on sales to local inter-business organizations, in return for which they receive tangible support including financing, training, research, development strategies and export efforts. [1]

The key to their success is working together with a deep understanding of the value of reciprocity, knowing that in so doing, they are building a co-operative network of strength and mutual obligation.

The same applies to the region’s actual cooperatives, which have their own support federations. A 3% levy on profits is paid to a Cooperative Development Fund and is used to start new co-ops, convert existing businesses into co-ops, and help existing co-ops grow and expand.

Local and regional governments play a critical role with supportive legislation, taxation and development initiatives, justified by the benefits that locally owned businesses and cooperatives bring to the economy. North American data shows that compared to non-local businesses, locally owned businesses recycle more income back to the local economy; are more reliable and stable; are more accountable; generate a stronger sense of local identity; their owners and staff engage more in civic activity; and they give more to local charities. [2]

I use the term ‘Regional Business Network’ to suggest a replicable form that could be built in every region as a foundation piece of the new economy.

2. A Strong Cooperative Support Network

The development of a strong cooperative sector needs additional emphasis. In Britain, the cooperative movement lobbied for good legislation in the 1960s, laying the foundation for the establishment of Cooperative Development Agencies which help groups of people who want to start a coop. Cooperatives UK, which promotes, develops and unites co-operative enterprises in Britain, has recently achieved the passage of even better legislation for Britain’s cooperative sector, whose 6,000 enterprises contribute in excess of $37 billion to the economy.

In Cleveland, Ohio, Evergreen Cooperatives was launched in 2008 by a working group of Cleveland-based institutions including the Cleveland Foundation, the Cleveland Clinic, University Hospitals, Case Western Reserve University and the municipal government, with the goal to create living wage jobs in low-income neighbourhoods using the purchasing power of these institutions to leverage a portion of the multi-billion dollar annual business expenditures of anchor institutions into the surrounding neighborhoods.

Their joint initiative has created three coops: The Evergreen Cooperative Laundry is a green laundry facility that provides linens for Cleveland hospitals, hotels, nursing homes and restaurants; Evergreen Energy Solutions designs, develops and installs solar panels; and Green City Growers Cooperative operates a 3.25-acre hydroponic greenhouse that sells fresh produce to grocery stores and food service companies in Cleveland and the surrounding areas.

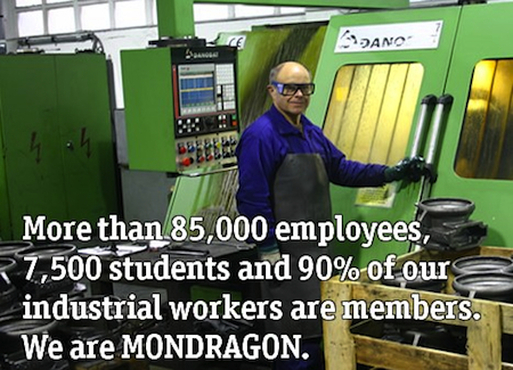

The most successful example of cooperative enterprise is the network of coops inMondragon, in the Basque region of northern Spain. As in Emilia-Romagna, their origins lie in anti-fascism, this time following the Spanish Civil War. When the local catholic priest, José Maria Arizmendiarreta, was confronted with poverty, hunger and hopelessness, he founded a technical college to provide training. He then asked himself a crucial question: “What does Jesuit teaching tell us about economic development?” The answers were “solidarity” and “helping each other,” which led him to the work of Robert Owen and Britain’s cooperative movement in the 19th century. Today, over 100,000 people work in three hundred Mondragon businesses, almost all of which are owned and managed cooperatively by their workers. They also have their own cooperative bank, university, business-start-up program and welfare system. [3]

3. Business Start-Up Support

The third initiative that is needed in every community is education, training and support to help people start new businesses, including youth, minorities, First Nations and low-income communities as well as regular folks. Enterprise lies at the core of every economy apart from a truly communal tribal economy, and this will be even more important in the emerging cooperative economy where we will need to spread and share the skills of enterprise. There are many models we can learn from, including the Kirklees Youth Enterprise Centre in Yorkshire, UK, which has helped 62 young people aged 14-19 to launch their own businesses after pitching to their own local Dragon’s Den.

In British Columbia, the Women’s Enterprise Centre helps women business owners create and grow their businesses. In 2013 they helped women to create 240 jobs. Since starting in 2009 they have provided $44 million in direct and leveraged financing, created almost $1.32 billion in economic activity, and they have a 75% success rate with their loan clients, 50% above the national average, generating 12 jobs per $100,000 lent.

In Manitoba, the First People’s Economic Growth Fund provides similar support to First Nations entrepreneurs, including help with community economic expansion loans and joint-venture investments. In BC, Ecotrust Canada has established a fund to support Aboriginal involvement in renewable energy hydro projects.

Learning how to run an enterprise needs to begin in our schools, so that young people can experience what it is like to run their own business or cooperative—actually doing it, not just receiving lessons about it. In Britain, every year Young Enterprise helps 250,000 young people to learn about business by doing it in teams, forming and running their own small micro-enterprises, helped by a network of 5,000 volunteers from 3,500 companies.

In 2012, a new initiative appeared: Startup Canada, a grassroots network of entrepreneurs which has quickly become the most active entrepreneurship organization in Canada. Since 2012 it has mentored more than 20,000 Canadians and engaged 400 enterprise support partners and 300 volunteers in a national network of 20 grassroots Startup Communities.

4. A Local Community Development Corporation

A community can organize to build its local economy by forming a community development corporation to gather finance, own shares, launch enterprises and create jobs and creating local wealth. There are many community development corporations (CDCs) in Canada, including innovative examples such as the Rainbow’s End CDC in Ontario, serving the greater Hamilton, Burlington, Ancaster, Stoney Creek and Dundas area, which operates six small social enterprises for people with mental health issues, including grounds maintenance and landscaping, painting, janitorial and clean-up, pick-up and delivery, sewing and flyer services.

New Dawn, in Cape Breton, is one of Canada’s longest running CDCs. It was founded in 1976 following the inspiration of the 1920s Antigonish Movement, when there was a similar drive to today’s to create a cooperative local economy. New Dawn is owned and controlled by people in Cape Breton, and it operates as a not-for profit social enterprise creating businesses to meet local needs, including a variety of nursing homes, health services, a dental clinic, a career college, the Cape Breton School of Crafts, half-way houses, a dozen rental housing projects, a Meals-on-Wheels service, and most recently the conversion of a big old school known as Holy Angels, built in 1858, into the New Dawn Centre for Social Innovation, which houses twenty businesses, community groups and service organizations. Since 2004, New Dawn has attracted $8.2 million in investments. It employs 175 people, and has its own RRSP-eligible Community Economic Development Investment Fund.

5. Community Banking

In Britain, credit unions are often tiny, hidden away in church basements, because their legal foundation is so weak. In Canada, by contrast, their legal foundation is strong and a city such as Vancouver benefits enormously from the presence of Vancity, a community owned credit union with $8 billion in assets, 58 branches and 490,000 members. Vancity contributes to the community in a host of ways, from helping aboriginal businesses to building affordable housing, from investing in food and farming and energy-saving initiatives to supporting local non-profits and social enterprises.

Canada is lucky in having strong credit unions—but many are run on traditional lines, in spite of their board members being elected democratically by their members. Vancity is only as good as it is because it has members who are actively engaged, and who work hard every year to ensure that progressive, community-minded people get elected to the board.

There are a myriad models for community banking, including the new wave of community banks being formed in Brazil, where 39% of the population does not have access to a bank account, and the hugely successful Grameen Bank founded in Bangladesh, which has become the inspiration for microlending banks all across the developed world. Like Vancity, Grameen is 100% owned by its members.

6. Microlending

Even with the best credit union or community bank there will be people who want to start an enterprise who lack the credit record or whatever else it takes to get a loan. This is where local microlending is so valuable for people on lower incomes. Community Microlending in Victoria is Canada’s first on-line peer-to-peer initiative. It matches local entrepreneurs without access to traditional financing to local lenders, along with the mentorship and support they need to start and grow their business; it also runs a youth program and an aboriginal program. It would be great to think that in a future cooperative economy no financial barriers of any kind inhibited the ability of someone to act on their passion to start a business, however poor or disadvantaged.

7. A Community Currency

Anyone can create money—it just needs trust. That’s where the word ‘credit’ comes from: the Latin verb credo, to believe. Money is created out of thin air, as an expression of trust. Banks do it all the time, and knowing this, communities around the world are organizing to create their own money, such as the Bristol Pound and the Brixton Pound in England, the Time Dollars schemes in America, the Banco Palmas in Fortaleza, Brazil, and theCheimgauer regional currency in Germany, which had over 555,000 Chiemgauers in circulation in 2012, a turnover equivalent to 6 million euros, and 600 participating businesses. 2400 people use the currency and more than 220 voluntary associations receive financial support through the scheme. All these experiments in currency strengthen people’s ability to participate in an economy, even when they have no conventional dollars to their name. Globally, the new wave of community currencies is being supported by the Dutch Social Enterprise Qoin and by the Community Currency Knowledge Gateway.

8. Inter-Business Cooperative Credit

Even in the best future cooperative economy there will still probably be booms and slumps, creating very real difficulties for businesses. In Switzerland, businesses faced this problem in the 1930s, as credit dried up and businesses were unable to buy the supplies they needed. The supplies were still there, but the credit needed to make the transactions was not. Rather than give up, however, a number of business owners realized that they owned enough collateral to bank a system of credit, and they created the WIR Bank, derived from the German word wirtschaftsring, or “economic circle” and the German word for “we”, signifying togetherness and solidarity.

Unlike other monetary experiments that started in the 1930s, WIR still operates in Switzerland, with some 60,000 small and medium enterprises participating. It has a stabilizing effect on Switzerland’s monetary system by providing a complementary source of funding when liquidity dries up, and it may be one of the secrets of the country’s financial success. The WIR Bank offers a full range of retail banking services, as well as cash savings accounts and loans to complement its WIR business. If in Switzerland—why not elsewhere?

9. Zero-Interest Mortgages

If you want to borrow $200,000 to buy a house at a fixed rate of 3% over 25 years, your payment will be close to $1,000 a month. Over 25 years you will pay $84,000 in interest. Interest worms its way into the cost of everything we buy, and is one of the major factors behind the seemingly relentless division of the world into the elite wealthy and “the rest”. In his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the French economist Thomas Piketty has shown in detail how when capital grows faster than the overall economy, inequity will always increase unless it is taxed accordingly.

It does not need to be this way, however. In Sweden, the JAK (“Land Labour Capital”) savings and loan co-operative is a members’ bank that has disconnected finance from compound interest, turning money from a store of value into a genuine medium of exchange that builds real wealth and sustainable and flourishing communities. To quote Michael Lewis and Pat Conaty, who wrote about the JAK Bank in their seminal book The Resilience Imperative: Co-operative Transitions to a Steady-State Economy:

“JAK is like a credit union, except that members do not earn interest on their savings or dividends on their shares. Instead, they earn one savings point per dollar they save. The maximum they can borrow is based on the number of points they have accumulated prior to a loan (pre-savings) and contract to accumulate after receiving a loan (post savings). Every loan is backed by the savings of JAK’s members. Members also can establish targeted savings accounts, or Local Enterprise Banks, to finance social or ecological enterprises.”

10. Benefit Corporations

So far, it might be reasonable to assume that businesses created through this new wave of community-based enterprise will be conventional businesses. They will create jobs and wealth, but unless something else changes, they will do so under the old model, where the prime goal of a business-owner—and the legally required goal of a corporate director—is to maximize profits.

This is a core value of free market capitalism, especially for legally incorporated businesses with external shareholders. Change that legal framework, however, and we have the foundation for a new kind of corporation: a B Corporation, or Benefit Corporation, which has a higher purpose other than simply maximizing profit.

In a B Corporation directors are legally required to deliver a social, community or environmental benefit as well as meeting financial goals. In October 2014 there were 1,128 B Corporations in 35 countries in 121 different industries, sharing one unifying goal: to redefine success so that it improves the quality of life for their workers, their community and the environment. Compared to other businesses, B Corporations are:

- 68% more likely to donate 10% of their profits to charity

- 47% more likely to use on-site renewable energy

- 18% more likely to use supplies from low-income communities

- 55% more likely to provide at least some health insurance costs for employees (in the US)

- 45% more likely to give bonuses to non-executive members, and

- 28% more likely to have women and minorities in management.

Put simply, the more local businesses become Benefit Corporations, the more the new local economy will deliver multiple social and environmental benefits, as well as profits.

11. Green Business Certification

A Benefit Corporation can be officially certified, like organic food, to prove that it is what it says it is. But what about a business that is not a B Corporation? If we are to avoid being driven over the cliffs of climate chaos and ecological collapse a future economy must be a green economy, and a green economy must be populated with green businesses.

In British Columbia, Canada, the Vancouver Island Green Business Certification program, established by the Synergy Sustainability Institute, has established a formal process of certification for an initial three sectors of the economy: retail, restaurants and offices. For each sector, a business must meet criteria that cover buildings and operations, waste, water, transportation, purchasing and products, climate change, and social dimensions, with points needed to achieve a Silver, Gold or Green level of certification.

So far the process is in its early days, with 11 certified restaurants, 16 certified offices, and 16 certified retail stores. In a future green cooperative economy we should expect green certification to be the norm, backed by supportive legislation and preferential purchasing.

12. A 100% Renewable Energy Region

The future economy must cease its dependence on fossil fuels, replacing it with 100% renewable energy for all purposes—electricity, transport and heat.

This is rapidly becoming a goal that nations, states, businesses and local governments are aspiring towards. In Germany, 53% of the country’s people live in a region that has officially set out to become a 100% renewable energy region, generating many new businesses and jobs.

For electricity, the transition requires the expansion of solar, wind, geothermal and other forms of renewable energy, combined with a strengthened effort to reduce energy usage and to store renewable energy in ways that balance the grid and enable firm power provision.

For heat, the transition needs an upgraded building code requiring every new building to be zero carbon, starting a few years hence. In Britain, the year is 2016 for all new homes, 2019 for buildings of every kind. In California, the equivalent rule is that every new single family home must be zero net energy, starting in 2020.

A new passive house needs 90% less heat than a conventional building, while costing much the same to build, and the small amount of heat needed can be met by a solar air-source or ground-source heat pump, or by seasonally stored solar thermal energy. All existing buildings need to be retrofitted to reduce their energy needs and to convert heat-sources to zero-carbon—a process that can generate many jobs and businesses.

For transportation, the transition needs a major effort to make our communities attractive and safe for pedestrians, to build thousands of new kilometres of safe bike lanes, to expand transit and light rail, and to adapt the auto-industry to electric cars, buses, trucks and bikes. Carsharing and bikesharing are important components, as Vancouver’s carshare coop Modo demonstrates. Some local trucking can go electric, while other local trucking can be shifted to cargo bikes, as Vancouver’s Shift Urban Cargo Delivery coop shows. Long-distance trucking is more problematic, since it will require a shift to biofuels, hydrogen or electric drive, a complex discussion that is outside the scope of this paper.

13. The Elimination of Student Debt

Some debt is essential to finance new projects and initiatives; other debt is destructive. Community banks and credit unions can teach financial literacy skills, as Vancity does, and Basic Income and affordable housing initiatives can reduce financial pressures, but when it comes to student debt, a more permanent solution is needed. Such a solution can either follow Germany’s and Scandinavia’s model, using high taxes to make higher education free, or Oregon’s proposed ‘Pay-It-Forward’ model, which would make higher education initially free, with graduate students paying 3% of their income for the cost of their education for 25 years, whether they work at Walmart or on Wall Street. A pilot program is being developed for consideration by the Oregon State Legislature in 2015.

14. Public Banking

Banking is the source of all money: credit is created by the simple act of advancing a loan, backed by the belief that it will be repaid. When a bank is confident that loans will be repaid it will issue loans to ten, twenty or thirty times the value of its assets, creating money out of thin air and earning interest on each loan.

In the words of Paul Tucker, Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, “… banks extend credit [make loans] by simply increasing the borrowing customer’s current account… That it, banks extend credit [make loans] by creating money.”[4]

- When a private bank creates money, the interest earned returns to its investors.

- When a credit union creates money, the interest earned returns to its members.

- When a public bank creates money, the interest earned returns to the public.

When a government owns a public bank it can use the credit it creates to finance appropriate economic development. It can charge lower rates of interest, and the interest earned returns to the public sector, adding to the government’s financial resources.

40% of all banks in the world are public banks—a fact that may appear astonishing in Britain, Canada and the US, where the unquestioned assumption that banking is private lies at the heart of the finance paradigm.

After the devastation of World War II, Germany used public banking to become one of the economic powerhouses of the world. Today, fully half of the assets in German banks are held in the public sector through thousands of Sparkassen municipal banks, cooperative savings banks, publicly owned real estate lenders, and eleven regional Landesbanks controlled by state governments which also operate as central administrators for the municipally owned savings banks. 432 public municipal savings banks and 1116 cooperative banks provide two-thirds of all lending to Mittelstand companies, 43% of lending to all companies and households, and 70% of domestic lending.

In 2011, only 28% of Germany’s banking was done through private banks—the rest was through public banks. Since 2011, however, following a hostile drive led by the European Commission and the European Banking Authority, Germany’s public banks have been stripped of the state guarantees that enabled them to issue credit at lower interest rates than private banks.[5

Germany, Switzerland, France, Spain, Portugal, Sweden, Norway, China, India, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Russia, Taiwan, South Korea and Costa Rica all have public banks of one kind or another. The economic miracles that were achieved in Japan in the 1950s and copied by Taiwan, South Korea and China were all facilitated in part by state investments using money created through public banking.

In Australia, for most of the 20th century the publicly owned Commonwealth Bank of Australia was the nation’s central bank. In Alberta, the publicly owned Alberta Treasury Branches provide financial services to 680,000 Albertans, serving 242 communities. In New Zealand, the publicly owned Kiwibank, established in 2002 and operating through the Post Office, has 800,000 customers.

There is no reason except ideological opposition why governments should not operate public banks, treating them like utilities to serve the public interest. In the US, North Dakota founded the publicly owned Bank of North Dakota in 1919 with $2 million in capital, and it has used it to good effect, being the only US state to have run a continuous budget surplus every year since 2008, to have the lowest foreclosure rate and the lowest credit card default rate in the country, and to have had no bank failures for at least a decade. North Dakota’s oil is a factor, but Alaska, Montana, South Dakota and Wyoming also have oil, and none has been able to copy North Dakota’s success. The bank provides a wide range of financial services, and over a 15-year period it has contributed more to the state’s finances than oil revenues.[6]

In November 2014, the Wall Street Journal did a story on the Bank of North Dakota in which they stated that “It is more profitable than Goldman Sachs, has a better credit rating than JP Morgan and Chase, and hasn’t seen profit growth drop since 2003. …Return on equity, a measure of profitability, is 18.56%, about 70% higher than those at Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan. . .”[7]

As the author and public banking campaigner Ellen Brown reports, the Bank of North Dakota takes deposits, issues loans, provides guarantees, and acts as a mini-Fed for the state, providing fund lines to other financial institutions. It also runs a loan program that allows local communities to provide assistance to borrowers for the purpose of job retention, technology creation, retail, small business, and essential community services. The state of North Dakota deposits its tax revenues in the bank, enabling it to issue loans which assist the state economy, and all revenues are returned to the state’s coffers, earning a healthy 19% return on equity in 2010.[8]

When a state or province does not have a public bank it is obliged to deposit its tax revenues with a private bank, which will invest them any way it wants, even in speculative schemes such as derivatives. It is only the ideology of free market capitalism that demands that private banks have a monopoly on the creation of credit.

A public bank can serve as a driver of loans and investment in the transition to a green cooperative economy, targeting growth sectors such as renewable energy, sustainable transportation, building retrofits, education, communications, energy efficiency, agriculture, value-added forest products, and the high-tech sector.

A Public Bank in any region, state or province could:

- Store government and crown agency revenues

- Create new money by the act of lending

- Save taxpayers up to 50% in interest costs on critical infrastructure like bridges, trains and schools

- Eliminate billions in bank fees and money management for cities and the province

- Support community bank loans to targeted areas of economic development, including clean energy, building retrofits, zero-carbon communities, farms, First Nations projects, value-added forestry, hi-tech, community development corporations, small businesses, students.

- Provide counter-cyclical relief by issuing credit at low or zero cost to revitalize infrastructure and other services

15. An Entrepreneurial State

In her seminal book The Entrepreneurial State the economist Mariana Mazzucato shows in detail how major commercial success stories such as Apple and Google were only possible because the US government played a supportive entrepreneurial role, investing in critical R&D leading to technology breakthroughs that private sector investors did not want to touch. All of the technologies that make the Apple IPhone so smart were government funded—the Internet, GPS, touch-screen displays, and SIRI voice activated responses. The same is true for solar and wind power, which depended on government-funded investments in R&D in America, Germany and China to achieve the breakthroughs that have led to so many successful companies today.

Mazzucato draws on the work of the economist Joseph Schumpeter to remind us that innovation is the force that drives success in an economy. She points to the critical role of Brazil’s publicly owned state investment bank, BNDES, which took bold risks in biotech and cleantech, earning a 21% return on equity for the state in 2010, at a time when the International Bank of Reconstruction and Development experienced a 2.3% loss.

This reminder of a historical truth is timely, since the transition into 100% renewable energy will require a maelstrom of R&D to crack critical problems and accelerate breakthroughs in zero-carbon home construction, zero-carbon long-distance transportation, battery capacity, rapid recharging, carbon-capture through farming and forestry, and so on.

16. New Ways of Measuring Progress

For decades, governments have measured the progress of their economies by adding up the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and pursuing growth in GDP. When an innovation led to increased productivity and market activity, it was counted in GDP; when there was a multiple pile-up on a highway all the insurance and repair costs also added to GDP; likewise, when a forest was stripped of its timber and left as a soil-depleted clearcut, the activity added to GDP.

GDP is a very crude measuring stick, equivalent to a business counting only its gains and not its losses. And increasingly, as economic activity extracts ecological wealth from nature, GDP stands for Gross Depletion of the Planet.

What matters to most people, however, is not simple wealth but simple happiness. The Danes, who pay among the highest rate of personal tax in the world, are routinely found to be among the happiest people in the world. In 2011 a Gallup poll asked 1,000 people in 148 countries if they were well-rested, had been treated with respect, smiled or laughed a lot, learned or did something interesting, and felt feelings of enjoyment the previous day. Seven of the ten countries with the most upbeat attitudes were in Latin America, many of which rate low for GDP.[9]

Using a different approach, the first ever World Happiness Report found that the happiest countries are in Northern Europe—Denmark, Norway, Finland and the Netherlands—where political freedom, strong social networks and an absence of corruption are considered as important as plain income, along with good mental and physical health, friends, job security, work-life balance and stable families.[10]

If it is happiness that people seek, the task of a government should be to optimize the conditions that enable them to experience happiness. In the new cooperative economy, all major economic decisions should be informed by their impact on those conditions, including social, environmental and cultural dimensions. The Genuine Progress Indicatoris one way to measure real progress defined in this way, and others will doubtless develop.

Conclusion

This has been a short and definitely incomplete list of some of the blocks that will be needed to build a green, cooperative, entrepreneurial economy at the local, regional and state level. Other changes will be needed at the personal level (changing the attitudes with which we shop, consume, invest, engage in our communities, and act when in positions of power); the national level (including changes to tax, welfare, Basic Income for every citizen, and new rules to govern bank behaviour); and the global level (including closing the tax havens, adopting new rules for corporate income reporting, replacing global free trade with global fair trade, introducing a Financial Transactions tax and a global tax on capital, and negotiating a firm global cap on carbon and a planned transition to a zero-carbon world.)

The challenge lies in the complexity of what’s needed: even to work on a single one of these sixteen blocks requires courage, knowledge and skill.

And furthermore, there is nothing inherent in a cooperative or democratic structure that guarantees responsible behaviour. Some co-ops behave like the worst businesses; some non-profits are managed as if by an autocrat; some community service organizations are run with incompetence and corruption. We cannot avoid the personal dimension of change, which requires training for the highest standards of ethics and responsibility, and a commitment to open, transparent governance, so that when bad things—which they will—they are not covered over, and the public is not kept in the dark.

There is a critical urgency to introduce these changes. With every month that passes global CO2 emissions rise, inequality grows and personal despair increases as people see no way to respond to the scale of adversity and grief that is approaching through climate change, ecological collapse and global financial collapse.

To address the urgency, we need two new initiatives:

First, we need an entity with the heart, the knowledge, the organizational capacity and the ability to form partnerships that is able to embrace the vision and get people around a table to make things happen. It may be an existing organization or it may be something new, such as a Green Cooperative Economy Alliance.

Second, we need a year-long educational and training initiative to train many hundred people to become familiar with these and similar initiatives and keen to become leaders, confident in the knowledge gained and the hands-on experience gathered.

During the years when the capitalist economy was being assembled constant leadership was exercised as blocks of the new economy were put in place. The very concept of life insurance, which is both capitalist and cooperative, was dreamed up and first implemented by two Scottish Presbyterian Ministers, Robert Wallace and Alexander Webster, who combined their love of mathematics with access to the first reliable population numbers on births and deaths. Their concern was the fate of the widows of ministers who were left with nothing to sustain them on the death of their husbands, for whom the poorhouse was often their only resort. It was these two people’s initiative that led to the establishment of Scottish Widows, which now holds free capital of £3.9 billion.

Building a green, entrepreneurial, cooperative economy is a huge worldwide undertaking. It is already underway, with building blocks such as the Grameen Bank being well established. It will be one of the great challenges of this century, motivating thousands to become innovators and leaders.

Our immediate tasks are to clarify and then to publicize the vision and to train its practitioners, so that when people ask the perennial question, “What is the alternative to capitalism?” they will be confident in their answer.

CCPA Goods Jobs Economy in BC Conference, November 21, 2014

The slides that accompany this presentation can be found here.

Guy Dauncey is a speaker, author, activist and eco-futurist who works to develop a positive vision of a sustainable future, and to translate that vision into action. He is founder and Communications Director of the BC Sustainable Energy Association, co-founder of the Victoria Car Share Cooperative, and author or co-author of nine books, including After the Crash: The Emergence of the Rainbow Economy (Greenprint, 1988, 1996) and The Climate Challenge: 101 Solutions to Global Warming (2009). He is completing a new book set in the year 2032 titled City of the Future: A Vision of a Better World. He is an Honorary Member of the Planning Institute of BC, and a Fellow of the Findhorn Foundation in Scotland. His websites are www.earthfuture.com and The Practical Utopian (https://guydauncey.wordpress.com).

[1] Emilia-Romagna. Prezi by Mitch O’Gorman. www.shareable.net/blog/region-in-italy-reaches-30-coop-economy

Economics, Cooperation and Employee Ownership. The Emilia Romagna Model, by John Logue. http://dept.kent.edu/oeoc/oeoclibrary/emiliaromagnalong.htm

How Successful Cooperative Economic Models Can Work Wonderfully… Somewhere Else. Frank Joyce, Alternet, July 23, 2013. www.alternet.org/economy/how-successful-cooperative-economic-models-can-work-wonderfully-somewhere-else

The cooperative economics of Italy’s Emilia-Romagna holds a lesson for the U.S.: In Bologna, Small Is Beautiful. Robert Fitch, The Nation, May 13, 1996.www.uwcc.wisc.edu/info/bologna.html

[2] Top 10 Reasons to Support Locally Owned Businesses. Institute for Local Self-Reliance.www.ilsr.org/why-support-locally-owned-businesses

The Small-Mart Revolution: How Local Businesses are Beating the Global Competition.Michael Shuman, Berrett-Koehler, 2007. www.bkconnection.com/ProdDetails.asp?ID=9781576753866

Local Dollars, Local Sense: How to Shift Your Money from Wall Street to Main Street. Michael Shuman, March 5, 2012. www.youtube.com/watch?v=jRwnx9wLEAE

The Benefits of Locally Owned Businesses. BALLE. http://bealocalist.org/economic-development/planet-protection/benefits-of-locally-owned-businesses

Locally owned businesses can help communities thrive — and survive climate change. Stacy Mitchell, Grist, April 26, 2013. http://grist.org/cities/locally-owned-businesses-can-help-communities-thrive-and-survive-climate-change/

Buying local twice as beneficial to economy: study. Business Vancouver, June 4, 2013.http://www.biv.com/article/20130604/BIV0102/130609985/-1/BIV/buying-local-twice-as-beneficial-to-economy-study

[3] Mondragon: www.mondragon-corporation.com

Basque co-operative Mondragon defies Spain slump. BBC News, Aug 13, 2013.www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-19213425

The MONDRAGON Cooperative Experience: Humanity at Work. Management Innovation Exchange, May 11, 2012. www.managementexchange.com/story/mondragon-cooperative-experience-humanity-work

[4] Do Banks Create Money? Positive Money. https://www.positivemoney.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Quotes_confirming_that_banks_create_money-1.pdf

[5] What We Can Learn from Germany: How Countries With Publicly Owned Banks Do Better Than America

Ellen Brown, Alternet, Oct 11, 2011.www.alternet.org/story/152736/what_we_can_learn_from_germany%3A_how_countries_with_publicly_owned_banks_do_better_than_america

[6] Can Public Banking Finance the New Economy? The Bank of North Dakota offers a model for public banking that could stabilize the economy. US News & World Report, Sept 27, 2012.www.usnews.com/opinion/blogs/economic-intelligence/2012/09/27/can-public-banking-finance-the-new-economy

[7] WSJ Reports: BND Outperforms Wall Streethttp://www.publicbankinginstitute.org/bnd_outperforms_wall_street

[8] North Dakota’s Economic “Miracle”—It’s Not Oil. Ellen Brown, YES Magazine, Aug 31, 2011. www.yesmagazine.org/new-economy/the-north-dakota-miracle-not-all-about-oil

[9] Happiest People On Planet Live In Latin America, Gallup Poll Suggests. Huffington Post, Dec 20, 2012. www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/12/20/happiest-people-on-planet-latin-america_n_2336772.html

[10] First World Happiness Report Launched at United Nations. Earth Institute at Columbia University, April 2, 2014. http://earth.columbia.edu/articles/view/2960