Despite their urgency, coronavirus outbreaks, health crises and failing institutions are just some of the problems our global society is facing today. Billions of people worldwide still lack access to healthy food, clean water and sanitation services — being unable to properly wash hands and stay safe in the midst of a pandemic. And we are still trapped in an economic system that fuels environmental damage, from biodiversity loss to climate change, which is threatening the quality and sustainability of life on Earth.

Now, more than ever, it is crucial that we rethink and redesign our modes of living and doing things in society. Permaculture, or “permanent culture” systems thinking, a set of ethical principles and DIY techniques, conceptualized by Australian scientist Bill Mollison, provides a way forward to address those issues. Mollison used to say that “although the problems of the world are increasingly complex, the solutions remain embarrassingly simple.”

Permaculture — a fusion of indigenous knowledge with modern science and technology — offers ways for people to meet their essential needs for food, water, sanitation and other non-material needs, with autonomy and harmony with nature. Its core ethical principles are: Earth Care, People Care and Fair Share. More importantly, it is a tool that anybody can make use of to be more resilient and to help overcome the critical challenges we are facing today.

Since its conception in the late 1970s, it has grown into a global grassroots movement. Permaculture is now practiced by hundreds of thousands of people, individually and in community, with projects being developed in more than 120 countries on all continents.

From powerlessness to positive change-making

“Permaculture offered me a positive way forward in a world where I’d wanted to change so many things,” said Aranya Austin, a trained permaculture practitioner and educator based in the United Kingdom. “When shown what we can do on a personal scale, our perspective changes from powerlessness to positivity.”

Aranya Austin’s permaculture teaching in action. (Learn Permaculture)

Aranya Austin’s permaculture teaching in action. (Learn Permaculture)

The most practical form to learn permaculture is by taking a Permaculture Design Course, or PDC. These courses aim to educate individuals and communities about how to grow their own food — using organic, biodiverse and low-cost methods. It also provides lessons on why and how to harvest rainwater, build waterless toilets, use renewable energies, develop composting and reusing skills, co-develop ethical communities and fair economies, and more.

Aranya has taught over 90 PDC courses throughout the U.K. since 2004. “Permaculture offers a grounding in many of the life skills we should have been taught at school,” he said. He also has a YouTube channel for those seeking to learn permaculture online, for free, and for those that currently must stay at home.

“One key skill we introduce is observation — something our fast-paced society tells us we don’t have time for,” Austin said. “Ironically, this is the very reason we’ve made such a mess of the world.”

In the United States, an educational organization called Permaculture Rising is on a mission to help people learn how to meet their needs for food, water, energy and other essentials in a resilient and environmentally sustainable manner. The educators, Andrew Millison and Marisha Auerbach, have taught over 100 PDCs across the Cascadia bioregion and abroad. Currently, they teach permaculture at Oregon State University and Portland Community College, including through online courses and free learning materials. (In this talk on SoundCloud, Millison and his guest discuss permaculture responses to the coronavirus pandemic.)

“We hope to offer ways that people can participate in lowering their carbon footprint, while engaging in their local environment and building community,” said Auerbach, co-founder of Permaculture Rising and a member of the Permaculture Institute of North America.

Auerbach explained that she also applies permaculture in her life and at home. Together with her partner, they grow about 80 percent of the food they eat, year-round, on an average-size urban backyard. They share surplus food and exchange seeds with neighbors and the local community. They also compost any organic waste they generate, storing carbon back into the soil and increasing its fertility.

The couple also collects rainwater for watering the garden and have a composting toilet to cut down on water use. They installed solar panels on their home, for a clean energy supply, and have a biodigester that allows them to cook with “biogas.” And while benefiting from a waste collection service at their doorstep, they almost never use it — as they rarely generate garbage, especially because packaged products and supermarket shopping is not a part of their routine.

When asked what motivated her to embrace this alternative lifestyle, Auerbach said that, given the critical problems people and the planet are facing nowadays, she consciously decided to be a part of the solution.

Turning problems into solutions

Permaculture encompasses a multitude of techniques that can be applied in small or large scale, in both rural and urban areas, and adapted to anywhere in the world. Yet it incorporates a universal mindset that problems can be turned into solutions — and ordinary people have the personal and collective power to do it.

Luwayo Biswick is one the many people that have benefited from Never Ending Food’s permaculture training in Malawi. He now grows almost 300 food crops on his land, which became a permaculture demonstration and learning site. (Permaculture Paradise Institute/Never Ending Food)

Luwayo Biswick is one the many people that have benefited from Never Ending Food’s permaculture training in Malawi. He now grows almost 300 food crops on his land, which became a permaculture demonstration and learning site. (Permaculture Paradise Institute/Never Ending Food)

In Malawi, in southeastern Africa, for example, a significant portion of the population has suffered from malnutrition, health problems and poverty. These conditions were mainly driven by agricultural policies that supported the production and consumption of maize, a crop native to Central America that has low nutritional value, while overlooking the local traditional and highly nutritious food crops. In an effort to overcome those issues, two permaculture designers together with community members created a project called Never Ending Food.

They have been cultivating over 200 traditional food crops, including medicinal plants, that now grow year-round, which is helping to boost nutrition, health and food resilience across the country. In parallel, smallholder farmers are able to diversify their sources of income and improve their livelihoods, because they do not need to expend money on imported seeds and industrial fertilizers anymore. Given the project’s success, Malawi’s national school curriculum has recently incorporated lessons on permaculture.

As risks of global food shortage have started to increase — driven by current coronavirus measures and climate change conditions — everybody in the world could benefit from learning permaculture, at least how to grow food at home or in their local area. But that’s easier said than done.

Robin Clayfield, who has been living for over 30 years in the Crystal Waters Permaculture Ecovillage in Australia, said there are two times of the year that are hard to grow food in the subtropics. One is during the wet season, because plants tend to rot with excessive humidity, and the other is in the dry season, when the water dries out. She explained that it has been very hard to keep plants growing in recent months due to the severe bushfires that spread across the country — a risk that’s increasing in Australia as the climate becomes drier and warmer.

Fortunately, the permaculture know-how that circulates in Crystal Waters is helping the community to adapt to climate change and obtain food and water resilience. Clayfield said most residents have raised beds in the garden, rainwater catchment tanks coming from their rooftops and use “swales” for land irrigation. These techniques are traditionally used by permaculture practitioners and can improve plant growing conditions, as well as better control water supply during flooding or drought seasons.

The Crystal Waters community, based in southeast Queensland, Australia, is currently formed by around 200 people of at least 16 nationalities. (Facebook/Crystal Waters Eco Village)

The Crystal Waters community, based in southeast Queensland, Australia, is currently formed by around 200 people of at least 16 nationalities. (Facebook/Crystal Waters Eco Village)

Clayfield mentioned that another challenge to her ability to be self-sufficient for food, is that it’s up to her to do most of the gardening on an acre of land, which is a lot of work for just one person. Yet living in a cooperative style of community can take some of the burden off individuals trying to do everything by themselves to meet their needs.

“In a permaculture village system we can look at how do we support each other,” Clayfield said. “And we can see who is doing what, so that we don’t have to do everything [individually].”

Monthly markets are organized in Crystal Waters, where residents of the village and nearby areas can buy and sell their local produce. There is also a bakery and coffee shop inside the village that are co-managed by residents, which support local access to food, income sources and social interaction (although they are currently closed due to the coronavirus quarantine in Australia).

Another strategy that the community uses is purchasing groups or bulk buying. Clayfield mentioned that they recently organized a bulk buying of solar-powered hot water systems, among 12 residents, getting it for a much more affordable price.

Besides doing things cooperatively, what seems to make the Crystal Waters community thrive is their approach to “sociocracy” and nature preservation — striving for a harmonious interaction between human beings, wildlife and the natural environment.

Pathway to a better future for all

Scientists who have studied the coronavirus disease have concluded that the virus originated in wildlife, probably in bats (that were sold in China’s live-animal markets), and then spread to humans. Studies have also shown that most epidemics that have emerged in recent decades — such as Malaria, Ebola, SARS, Lyme disease and hundreds more — were caused by the increasing human-wildlife conflicts and destruction of natural habitats. That means the best way to prevent the emergence of infectious diseases is by preserving nature and biodiversity.

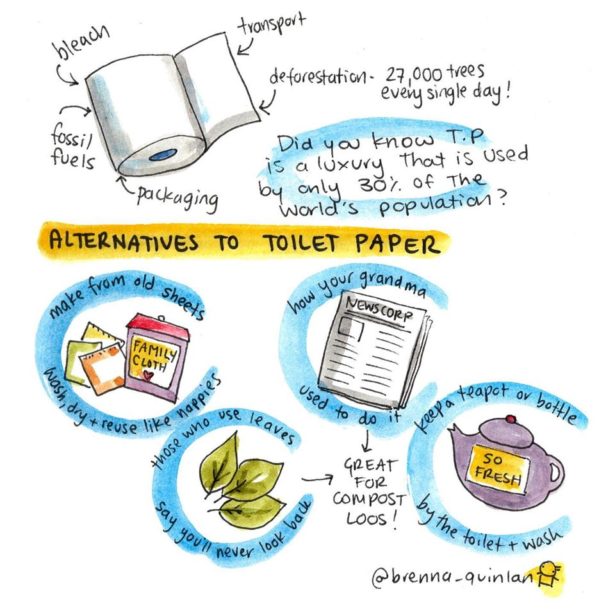

But the preservation of nature requires profound changes to how humans produce and consume resources in the modern age. Fortunately, permaculture can guide people on co-creating those essential changes. This “indigenous science” can also empower individuals to get more resilient during and after the pandemic — with lessons on how to grow food at home to exploring alternatives to toilet paper use.

Alternatives to toilet paper use, by Brenna Quinlan, a permaculture illustrator. (Facebook/Brenna Quinlan)

Alternatives to toilet paper use, by Brenna Quinlan, a permaculture illustrator. (Facebook/Brenna Quinlan)

Permaculture is empowering people to transition from passive consumers — dependent on structurally unhealthy, unjust and unsustainable socioeconomic systems — to active citizens and problem-solvers. Its transformative potential has no boundaries, as long as people don’t lose inspiration and the willingness to try something different.

“One could lose inspiration, but I never do,” Clayfield said, while reflecting about the challenges of cultivating an alternative, permaculture lifestyle. “I do it for my own sanity and to offer positive solutions to our world.”

Marina Martinez is a Brazilian biologist, environmental scientist and freelance writer. Her writing covers issues related to health, sustainable development, political economy and sociocultural transformation. She blogs on Medium @MarinaTMartinez