Singapore City’s skyline. May_Lana/Shutterstock

Climate breakdown, mass extinctions, and extreme inequality threaten the earth’s rich tapestry of life and leave our own fate increasingly uncertain. At a time of such social, political and ecological upheaval, it’s natural to dream of a utopian world in which these problems are no more – in fact, people have been doing it for centuries.

Such visions are often dismissed as nothing more than pointless flights of fancy, yearnings for impossibly perfect societies. But these assumptions are largely incorrect. Utopianism is the lifeblood of social change, and has already inspired countless individuals and movements to change the world for the better.

Utopia is not, as its Greek etymological roots suggest, a “no-place”. The name may derive from Thomas More’s classic 16th-century fictional work, Utopia, but it is not confined to literature depicting distant or fantastical ideal worlds.

Utopianism is in fact a philosophy that encompasses a variety of ways of thinking about or attempting to create a better society. It begins with the seemingly simple yet powerful declaration that the present is inadequate and that things can be otherwise. Present in communities, social movements, and political discourse, it critiques society and creatively projects futures free of the strangleholds of the time. Put simply, it embodies a longstanding human impulse towards self-improvement.

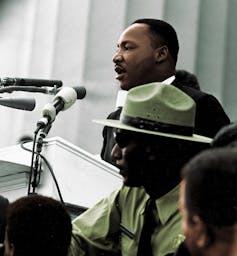

‘I have a dream..’ Emijrp/Bureau of Public Affairs

‘I have a dream..’ Emijrp/Bureau of Public Affairs

Utopianism is manifest in countless historical examples of those that have dared to challenge the status quo and assert that things can – and indeed, must – change. Take Martin Luther-King’s dream of a world free of racial segregation for example, or the strivings of the suffragettes for gender equality.

Ecological utopia

Now, our relationship with the natural world is humanity’s defining challenge – and utopian ideas have shifted to meet it. “Ecotopian” aspirations are already in full view in community networks attempting to create more conscious ways of living such as the Transition Network, social movements such as Extinction Rebellion, and bold policy proposals such as the USA’s Green New Deal. What’s more, many of the ideas put forth by these projects were long since imagined in prominent ecotopian literary works.

In the ideal worlds sketched in Ernst Callenbach’s Ecotopia and Kim Stanley Robinson’s Pacific Edge for example, resources are renewably sourced and communally owned. Healthcare, education, and meaningful employment are available to all. Extreme wealth disparities have been eradicated through income caps and minimum earnings schemes. These ideas are reflected in many aspects of the Green New Deal, which aims to transition the USA towards communal ownership of energy systems and a 100% renewable energy system by 2030, as well as enshrine into law rights to single-payer healthcare, guaranteed work at a living wage, affordable housing, and free university education.

It’s not clear whether Alexandro Ocasio-Cortez, the leading figurehead for the grand policy package, was directly inspired by these works. But judging from the way she has been promoting the Green New Deal, she certainly sees the value in painting visions of utopia. For example, her viral video, titled “A Message from the Future”, creatively imagines a more socially and ecologically resilient society just a few decades on from now – and, crucially, helps us to believe that it is possible.

As a decentralised global movement that gives its members autonomy and demands politics in which citizens lead, Extinction Rebellion also echoes ideals from ecotopian novels. In Ecotopia and many other similar works, most aspects of life are decentralised, from small-scale agriculture to neighborhood-specific healthcare. In Pacific Edge, the direct brand of politics Extinction Rebellion advocates is central to social and ecological wellbeing.

Extinction Rebellion urges efforts of wartime proportion to decarbonise by 2025 – a utopian target that has been met with scepticism in some quarters. But whether or not it is achievable, such a demand has been crucial in highlighting that what is presently deemed politically possible is not sufficient to stop catastrophic climate breakdown.

Their radical visions have shifted the climate and ecological crises to the forefront of the political agenda. And, crucially, they have switched millions on to the idea that fundamental transformations in the way we organise and power our societies are possible.

To some, the serious political proposals outlined by Extinction Rebellion and in the Green New Deal might seem as unrealistic as the literary works that imagine their realisation. But living examples of ecotopian imagination can already be found in the world we live in.

Thousands of intentional communities across the globe are already creating spaces with social and ecological justice at their heart. Many of these eco-communities have been directly inspired by the communities imagined in ecotopian novels. For example, hundreds of eco-villages in the Baltic region were set up according to the concept laid out in Vladimir Megre’s The Ringing Cedars of Russia.

A Latvian ecovillage based on The Ringing Cedars of Russia. Santa Zembaha/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

A Latvian ecovillage based on The Ringing Cedars of Russia. Santa Zembaha/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Some movements, such as the Transition Network – whose co-founder describes himself as a “vision harvester” – are even working to transform existing settlements across the world, with great success. As just one example among initiatives in nearly 1,000 towns and cities, Transition Marlborough’s Bee Roadzz project in south-west England has drawn together local residents, businesses and organisations to link habitats and combat the rapid decline of bees and other pollinators.

In shattering the perceived rigidity of the present, utopianism paves the way for change. Perfect worlds may not be realisable or even desirable, but that doesn’t mean we should shy away from imagining and striving for a better future. Societies without extreme inequality and environmental degradation are surely within the bounds of possibility. Whether in the form of a creative novel, a social movement, or a political proposal, dreaming can help us get there.

Click here to subscribe to our climate action newsletter. Climate change is inevitable. Our response to it isn’t.

Heather Alberro, Associate Lecturer/PhD Candidate in Political Ecology, Nottingham Trent University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.