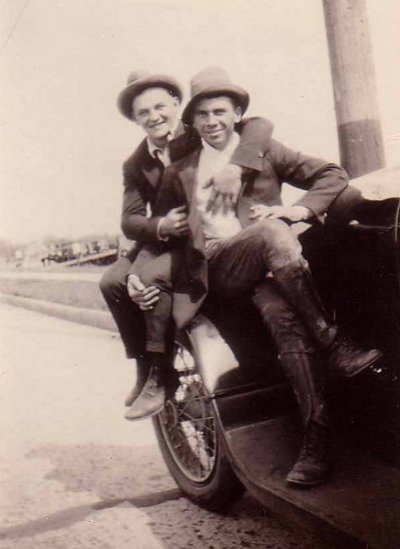

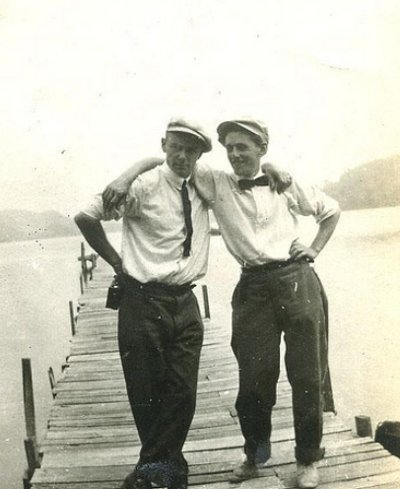

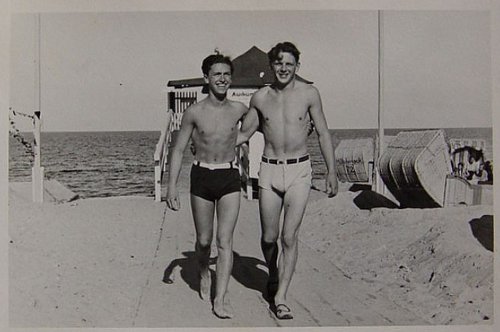

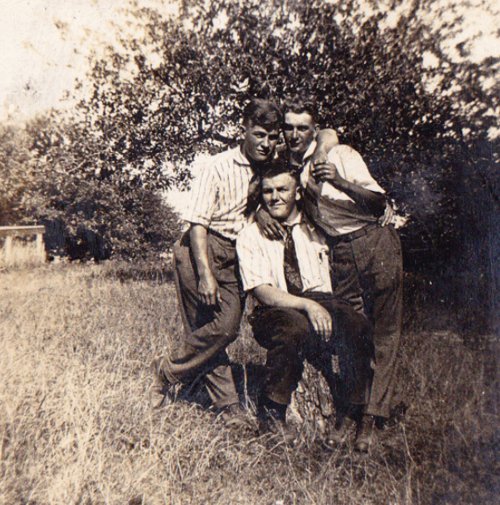

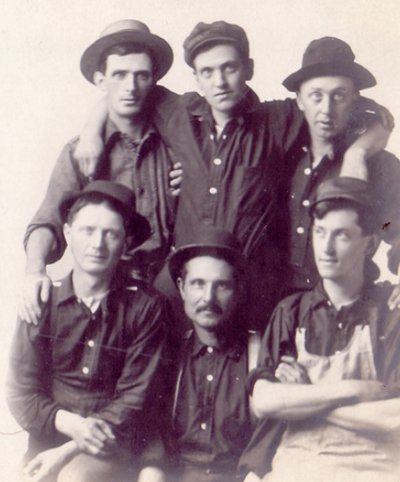

In my unending search for just the right vintage images for our articles, I have looked through thousands of photographs of men from the last century or so. One of the things that I have found most fascinating about many of these images, is the ease, familiarity, and intimacy, which men used to exhibit in photographs with their friends and compadres.

I shared a handful of these images in our very early post on the history of male friendship, but today I wanted to share almost 100 more in order to provide a more in-depth look into an important and highly interesting aspect of masculine history: the decline of male intimacy over the last century.

As you make your way through the photos below, many of you will undoubtedly feel a keen sense of surprise — some of you may even recoil a bit as you think, “Holy smokes! That’s so gay!”

The poses, facial expressions, and body language of the men below will strike the modern viewer as very gay indeed. But it is crucial to understand that you cannot view these photographs through the prism of our modern culture and current conception of homosexuality. The term “homosexuality” was in fact not coined until 1869, and before that time, the strict dichotomy between “gay” and “straight” did not yet exist. Attraction to, and sexual activity with other men was thought of as something you did, not something you were. It was a behavior — accepted by some cultures and considered sinful by others.

But at the turn of the 20th century, the idea of homosexuality shifted from a practice to a lifestyle and an identity. You did not have temptations towards a certain sin, you were a homosexual person. Thinking of men as either “homosexual” or “heterosexual” became common. And this new category of identity was at the same time pathologized — decried by psychiatrists as a mental illness, by ministers as a perversion, and by politicians as something to be legislated against. As this new conception of homosexuality as a stigmatized and onerous identifier took root in American culture, men began to be much more careful to not send messages to other men, and to women, that they were gay. And this is the reason why, it is theorized, men have become less comfortable with showing affection towards each other over the last century. At the same time, it also may explain why in countries with a more conservative, religious culture, such as in Africa or the Middle East, where men do engage in homosexual acts, but still consider homosexuality the “crime that cannot be spoken,” it remains common for men to be affectionate with one another and comfortable with things like holding hands as they walk.

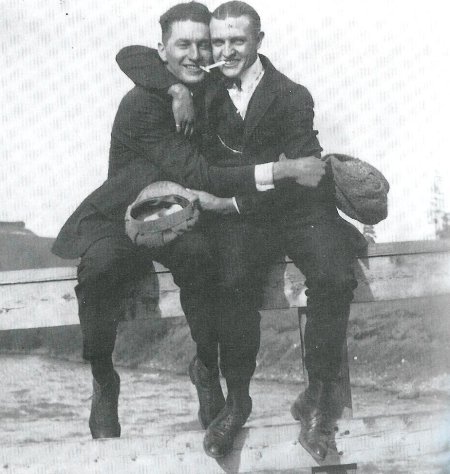

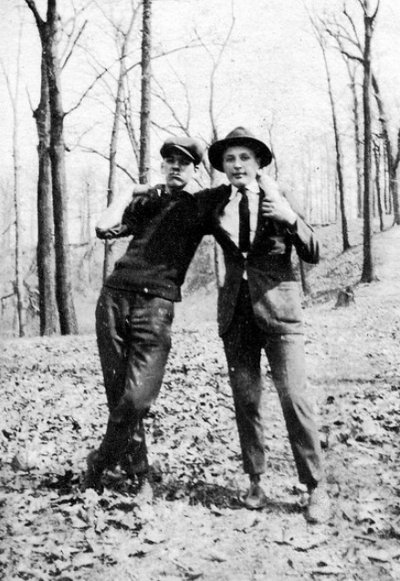

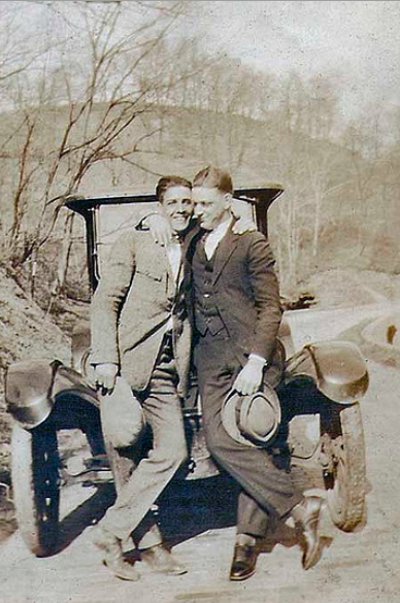

Whether the men below were gay in the way our current culture understands that idea, or in the way that they themselves understood it, is unknowable. What we do know is that the men would not have thought their poses and body language had anything at all to do with that question. What you see in the photographs was common, not rare; the photos are not about sexuality, but intimacy.

These photos showcase an evolution in the way men relate to one another — and the way in which certain forms and expressions of male intimacy have disappeared over the last century.

It has been said that a picture tells a thousand words, so while I have provided a little commentary below, I invite you to interpret the photos yourselves, and to ask and discuss questions such as: “Who were these men?” “What was the nature of their relationships?” “Why has male intimacy decreased and what are the repercussions for the emotional lives of men today?”

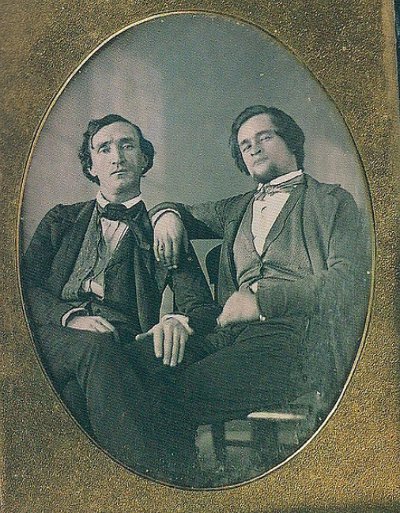

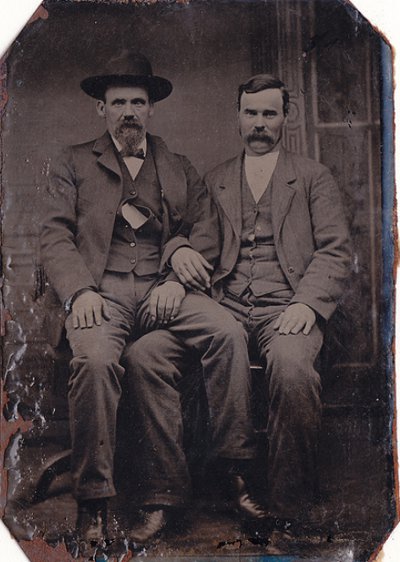

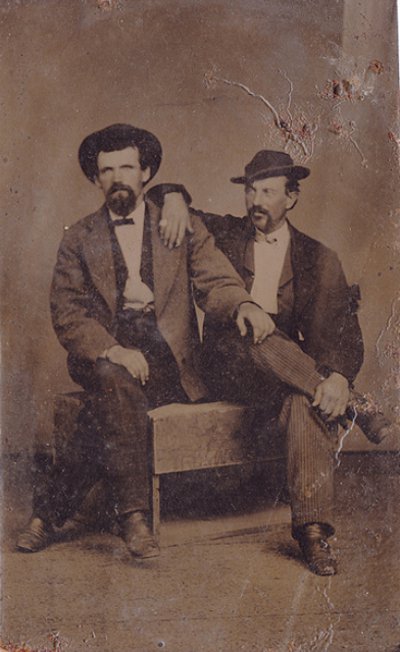

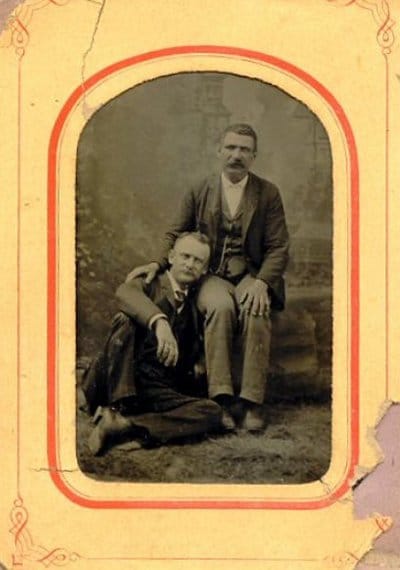

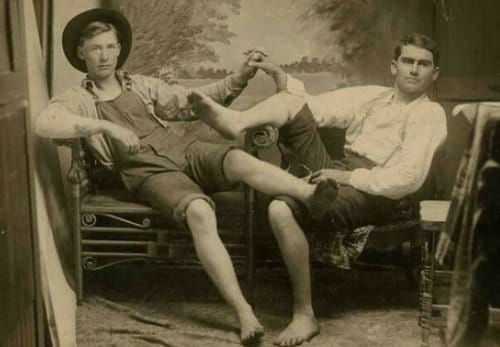

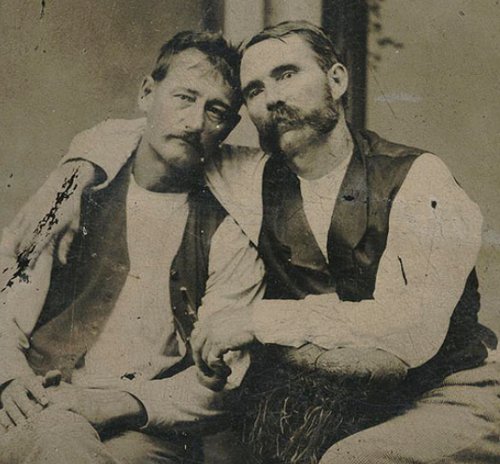

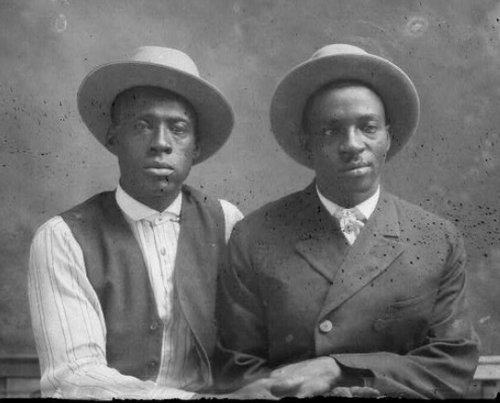

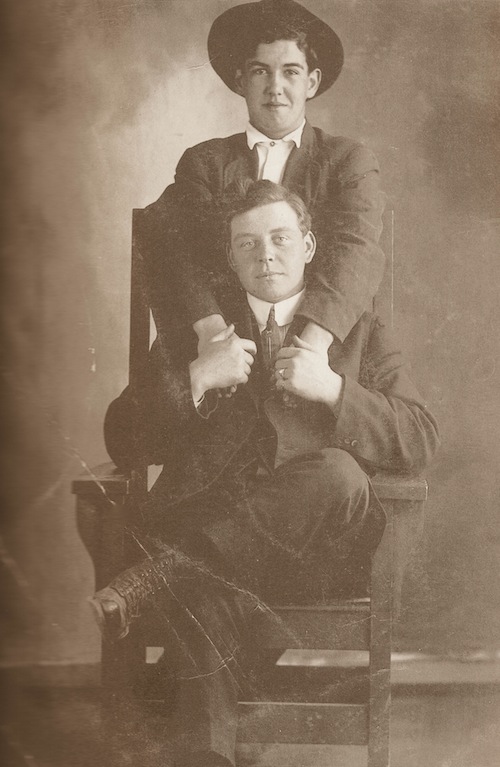

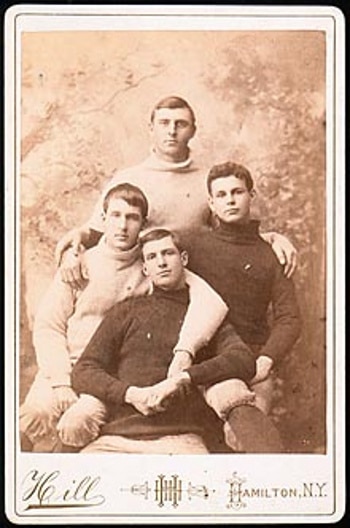

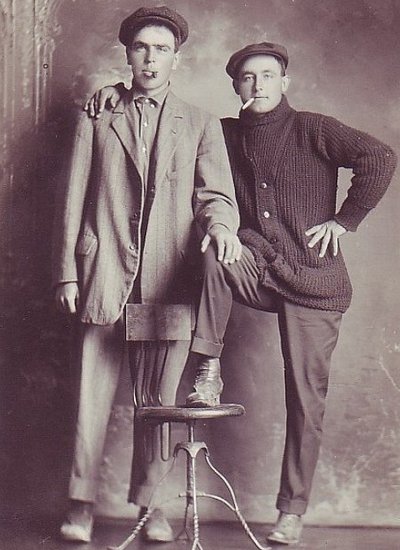

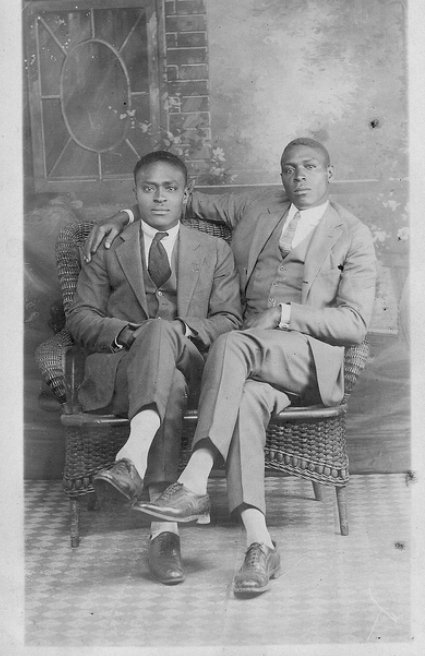

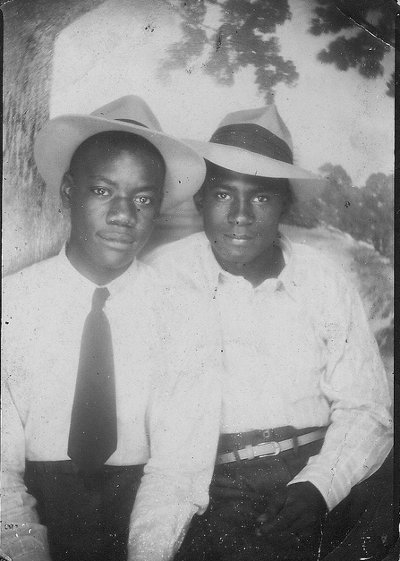

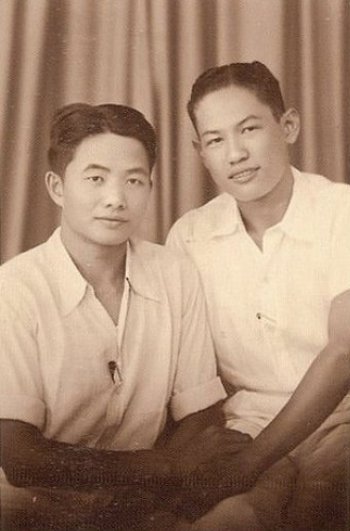

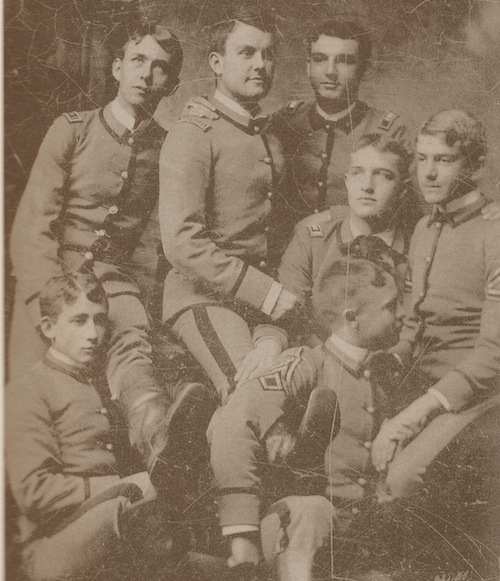

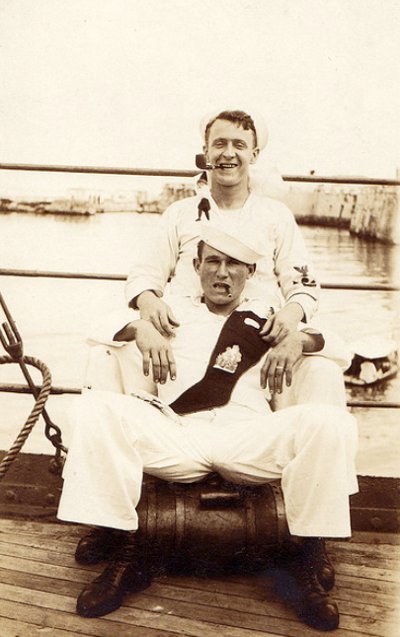

Men as Friends

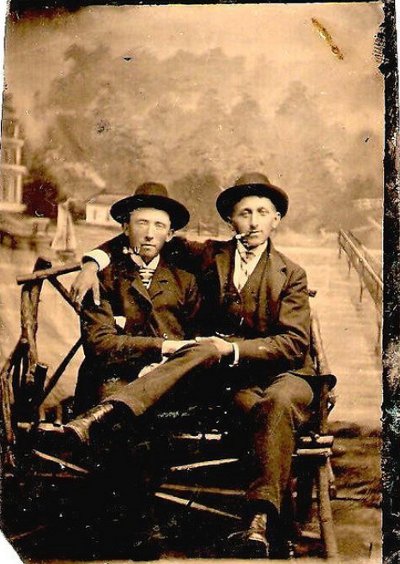

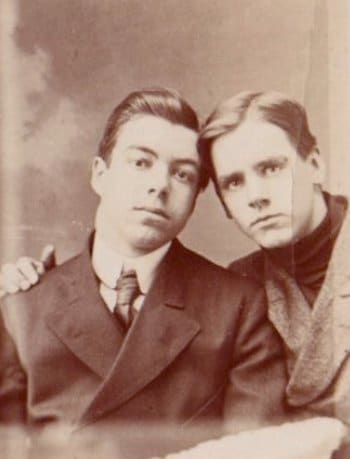

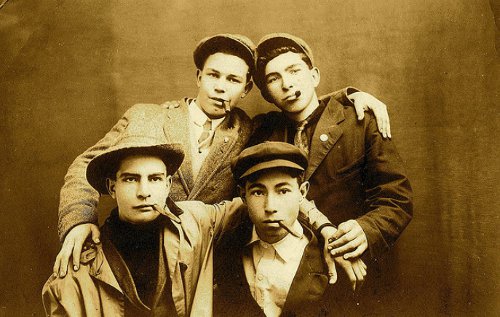

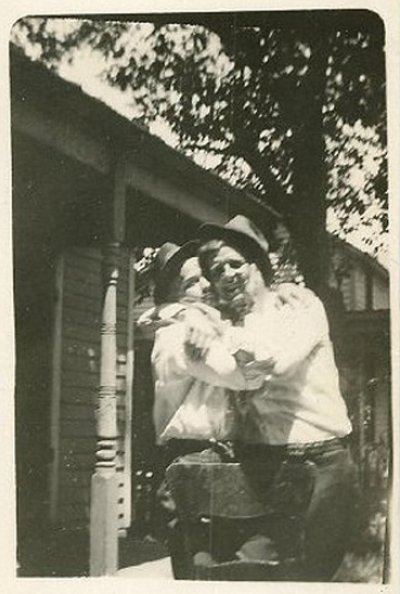

From the Civil War through the 1920′s, it was very common for male friends to visit a photographer’s studio together to have a portrait done as a memento of their love and loyalty. Photographers would offer various backgrounds and props the men could choose from to use in the picture. Sometimes the men would act out scenes; sometimes they’d simply sit side-by-side; sometimes they’d sit on each other’s laps or hold hands. The men’s very comfortable and familiar poses and body language might make the men look like gay lovers to the modern eye — and they could very well have been — but that was not the message they were sending at the time. The photographer’s studio would have been at the center of town, well-known by everyone, and one’s neighbors would having been sitting in the waiting room just a few feet away. Because homosexuality, even if thought of as a practice rather than an identity, was not something publicly expressed, these men were not knowingly outing themselves in these shots; their poses were common, and simply reflected the intimacy and intensity of male friendships at the time — none of these photos would have caused their contemporaries to bat an eye.

When the author of Picturing Men, John Ibson, conducted a survey of modern day portrait studios to ask if they had ever had two men come in to have their photo taken, he found that the event was so rare that many of the photographers he spoke to had never seen it happen during their career.

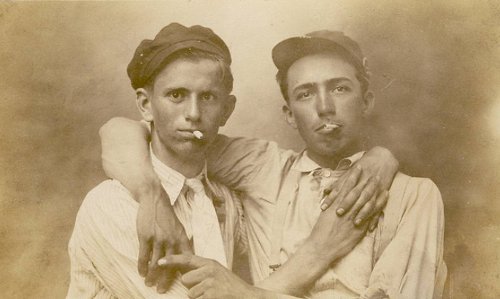

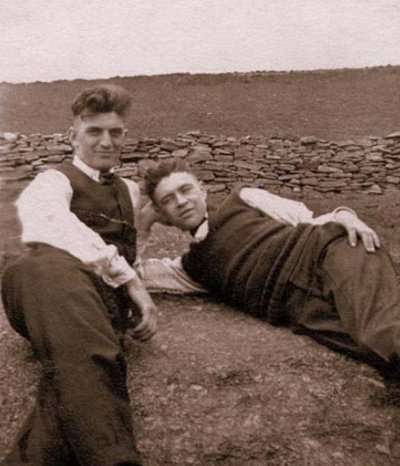

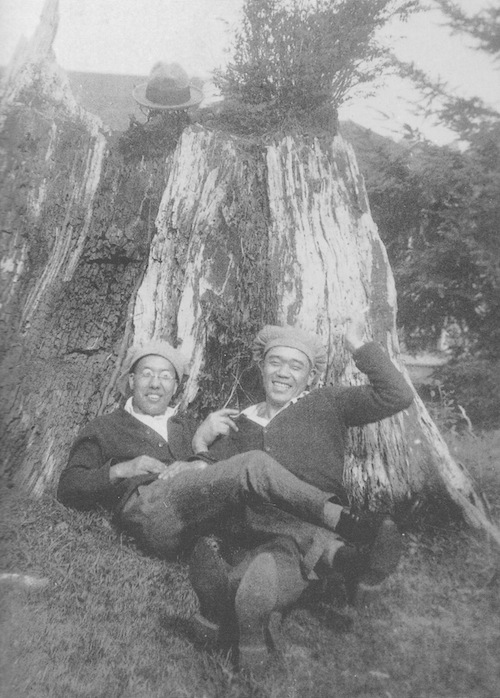

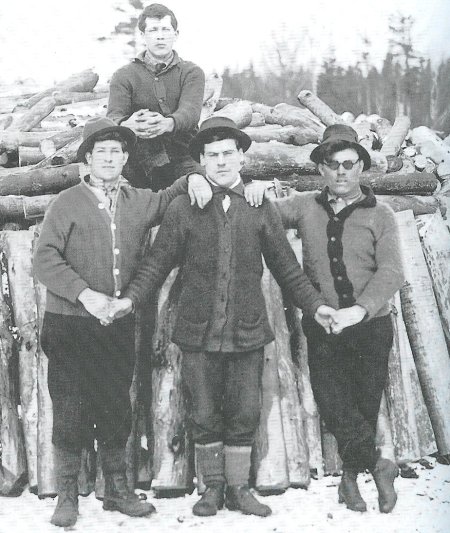

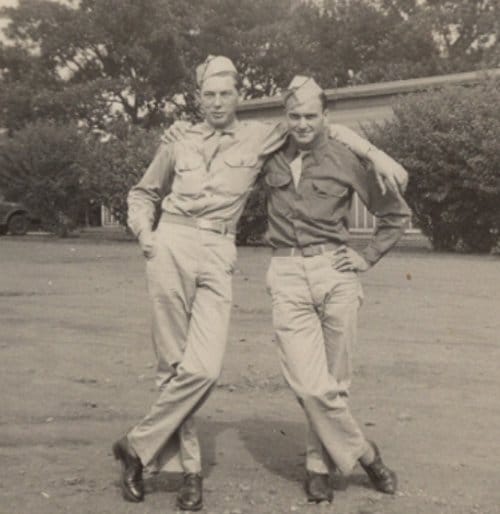

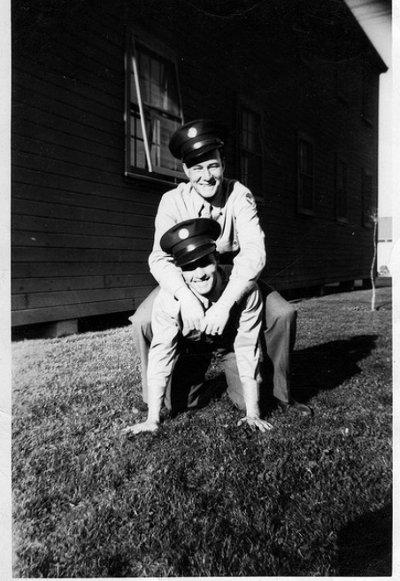

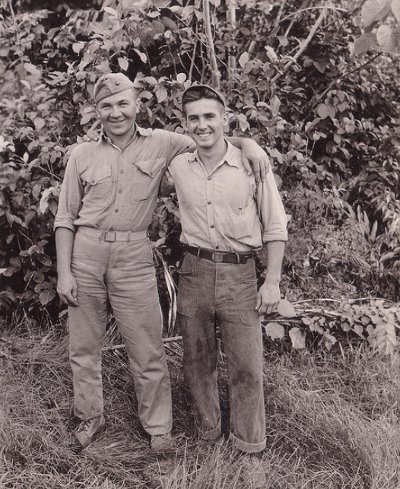

Snapshots

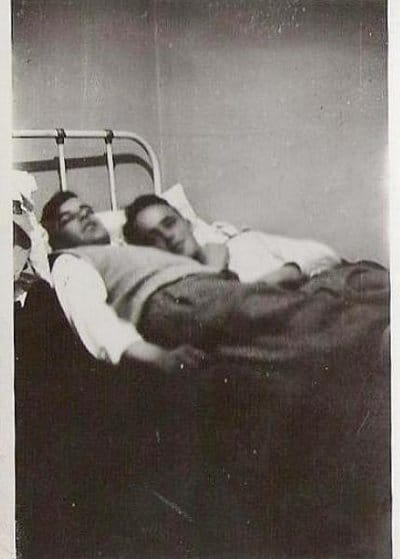

When portable cameras for the amateur photographer became more widely available, they allowed men to photograph themselves in a greater range of more spontaneous situations, and the practice of sitting for formal portraits together waned in the 1930s. The snapshots usually were developed by someone else who would have gotten a look at all of them, so again, these pictures were not likely purposeful expressions of gay love, but rather captured the very common level of comfort men felt with one another during the early 20th century.

One of the reasons male friendships were so intense during the 19th and early 20th centuries, is that socialization was largely separated by sex; men spent most their time with other men, women with other women. In the 50s, some psychologists theorized that gender-segregated socialization spurred homosexuality, and as cultural mores changed in general, snapshots of only men together were supplanted by those of coed groups.

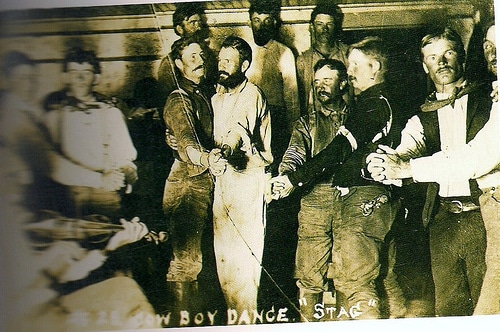

In all male environments, such as mining camps or navy ships, it was common for men to hold dances, with half the men wearing a patch or some other marker to designate them as the “women” for the evening.

Forming pyramids on the beach was a popular pastime for men through the 30s.

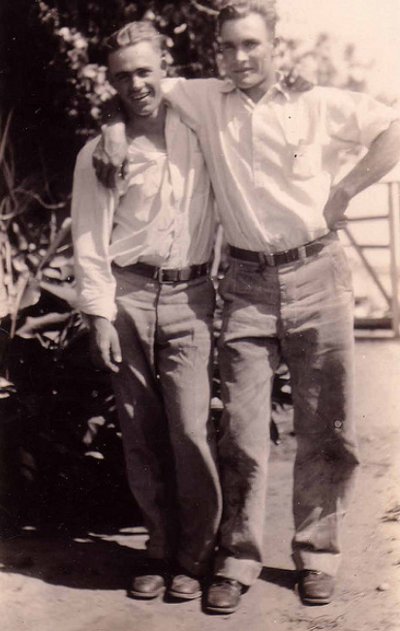

After WWII, casually touching between men in photographs decreased precipitously. It first vanished among middle-aged men, but lingered among younger men. But in the 50s, when homosexuality reached its peak of pathologization, eventually they too created more space between themselves, and while still affectionate began to interact with less ease and intimacy.

After WWII, casually touching between men in photographs decreased precipitously. It first vanished among middle-aged men, but lingered among younger men. But in the 50s, when homosexuality reached its peak of pathologization, eventually they too created more space between themselves, and while still affectionate began to interact with less ease and intimacy.

It’s not true that American men are no longer affectionate with each other at all. Hand-holding and lap-sitting are out, but putting your arms around your buddies is still common. Physical affection seems more common among high school and college age men, a time when friendships are closer, than among middle-aged men, and this has probably always been the case more or less. Although it may also have to do with generational and cultural changes, as we’ll touch on at the end of the article.

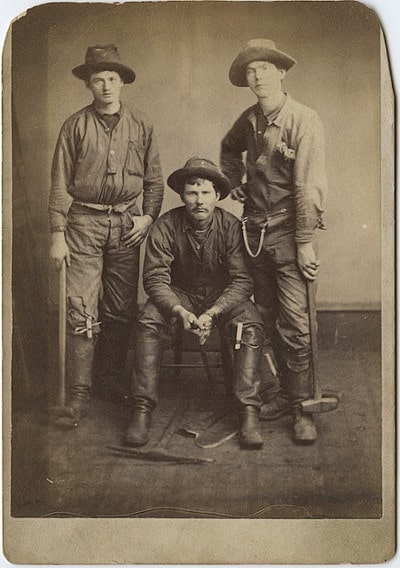

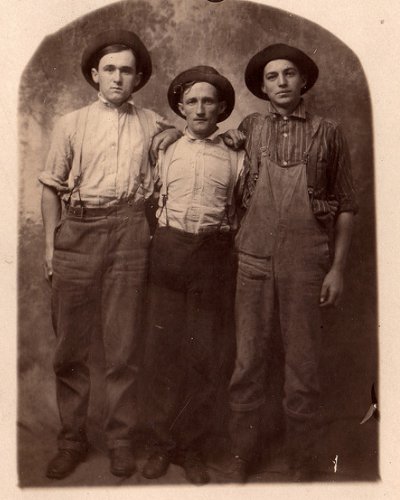

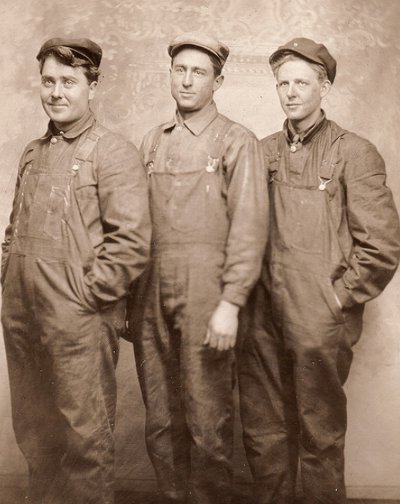

Men at Work

It was also popular for men to get portraits done with the guys they worked with, often while wearing their work clothes — from aprons to overalls — and holding the tools of their trade — from frying pans to hammers. That men wished to immortalize themselves alongside their “co-workers” shows how important work was to a man’s identity and the close bond men used to feel with those they shared a trade with and toiled next to.

When a photo studio wasn’t nearby, snapshots were taken. These snapshots reveal the camaraderie men felt with those they worked beside.

As the trades waned in importance, and white collar work waxed, photographs of men on the job became more formal and less intimate. Instead of seeing each as fellow craftsmen, working for a common goal with a shared pride in the work, men became competitors with each other, each trying to get ahead in a dog-eat-dog world. And a lot less work-related photographs were taken in general. Perhaps because we only take photographs of pleasurable things, things we want to always remember, and the pleasure men took in their work had fallen.

“Enforced mobility of work groups, the resultant discontinuity in personal relations–sometimes even the wife won’t go with you–perhaps explains the unwillingness of modern individuals to embark on intense friendships. What is the point of having a ‘best friend’ or ‘blood brother’ if you are constantly changing jobs and flats?” –Robert Brain

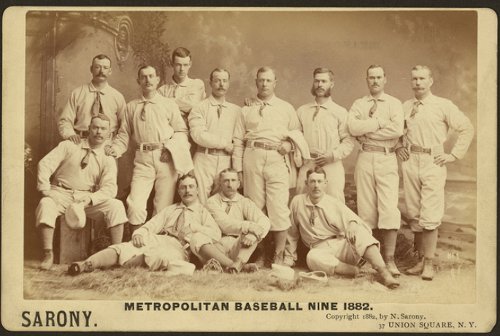

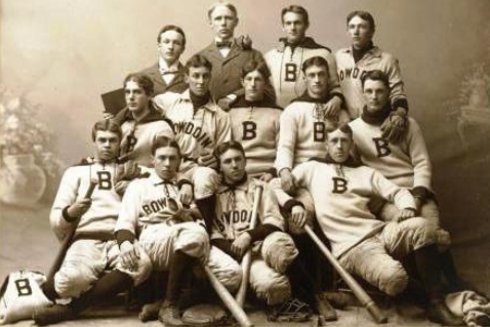

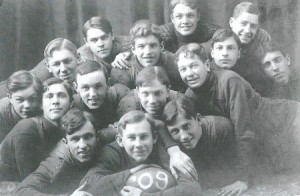

Men on the Field

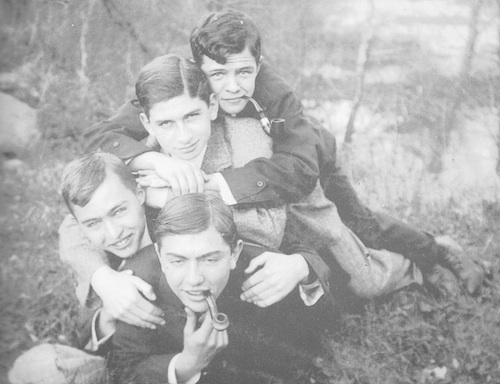

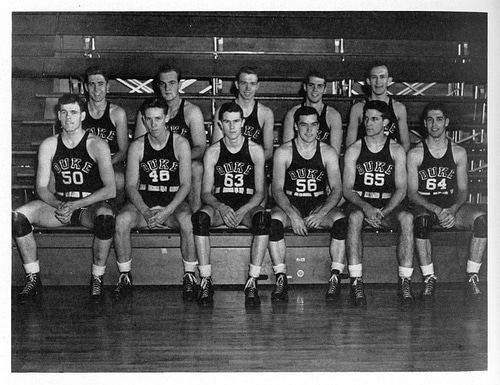

As team sports became one of the great passions of a man’s life in the 1890s, the team photo became a required ritual. A team wished to have a memento of the exploits of the season, and no yearbook was complete without one. The changing poses of the team photo provide a window into the evolving mores of male affection, and perhaps into the evolving nature of sport itself.

At the turn of the century, team photos were more intimate and casual, with teammates piling on top of one another, leaning on each other, and draping their arms around one another.

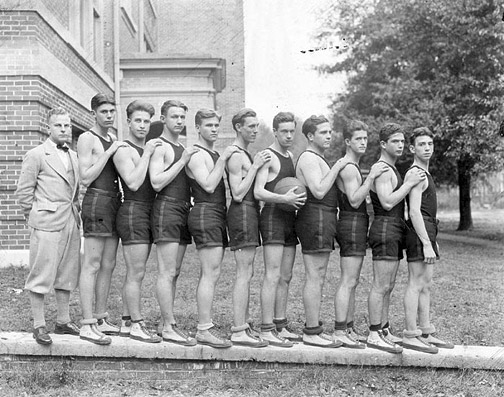

1915 basketball team

Starting in the 1920s, team photos became more formal, more like the team photos we know today. Instead of touching each other, the men crossed their arms across their stomach or put them behind their backs. Each player stood more isolated from the others, much as the space between businessmen had grown as well. Still a team, but a team of distinct individuals.

Duke basketball team 1942-43

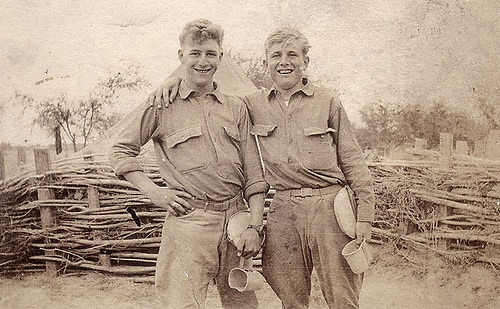

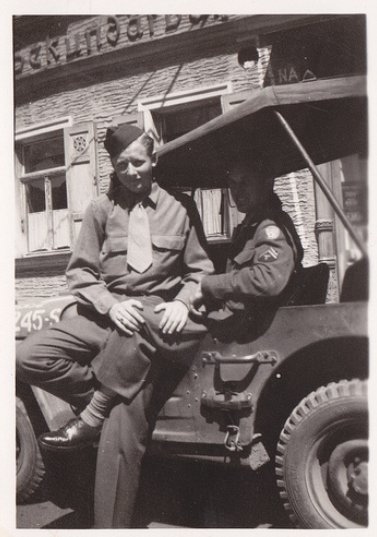

Men at War

Some of the most intense bonds between men have always been found among those who serve in the military. Gender segregation (at least in times past), is at its very highest. Men are far from home and can only rely on each other; together they face the highest dangers and are motivated less by duty to country and more by the desire not to let their brothers down. Serving is such an unquestionably manly thing, that homophobia dissipates; soldiers care less about one’s sexuality than whether the man can get the job done.

The man who served in WWII and experienced intense camaraderie with his battlefield brothers, often had trouble adjusting to life back home, in which he got married, settled in the suburbs, and felt cut off and isolated from other men and the kind of deep friendships he had enjoyed during the war.

My Buddy

Life is a book that we study

Some of its leaves bring a sigh

There it was written by a buddy

That we must part, you and I

Nights are long since you went away

I think about you all through the day

My buddy, my buddy

Nobody quite so true

Miss your voice, the touch of your hand

Just long to know that you understand

My buddy, my buddy

Your buddy misses you

Miss your voice, the touch of your hand

Just long to know that you understand

My buddy, my buddy

Your buddy misses you

Your buddy misses you, yes I do

Written in 1922 by Walter Donaldson, “My Buddy” was originally inspired by the heartbreaking death of Donaldson’s fiancee, but was adopted during WWII by the troops as a way to express their deep attachment to each other.

Today’s serviceman enjoys the same intense bonds as his forebearers did. But, at least in photographs, he is much less likely to express this bond in overt ways. The most common pose among today’s soldiers is standing side-by-side, holding one’s weapons.

Conclusion: What Is the Future of Male Intimacy?

“Boys imitate what they see. If what they see is emotional distance, guardedness, and coldness between men they will grow up to imitate that behavior…What do boys learn when they do not see men with close friendships, where there are no visible models of intimacy in a man’s life beyond his spouse?” -Kindlon and Thompson, Raising Cain

Sociologists have noticed that Millennial boys seem much more comfortable with showing affection for each other than their fathers did. According to an article in The New York Times, whereas their parents might have given each other a high five, hugging has become the de facto way for teenagers to greet each other and to part ways — even to the point that non-huggers are viewed warily — and is as common among boys as girls. “We’re not afraid, we just get in and hug,” said Danny Schneider, a high school junior who was interviewed for the story. Some theorize that Millennial boys have become more comfortable with touching because their generation is less cynical and more cooperative and group-oriented.

Others posit that because so much of young people’s socialization is done online, they have a deeper need to physically connect in person to balance things out. And it may also be traced to the culture’s greater acceptance of homosexuality, although that has in turn solidified being gay as an identity, and it seems unlikely that men will cease wanting to communicate to others whether they are homosexual or heterosexual anytime soon. It also seems unlikely that in a transient and very coed, non gender-segregated society, male friendships will ever be as intense as they once were. Although even that is changing: twenty-somethings are much less likely to move these days than they have been in decades.

So what do you think is the future of male intimacy? What thoughts came to you as you looked at these photos? I know AoM has readers from all over the world, so fill us in on how men interact in your neck of the global woods.

______________

Source:

Picturing Men: A Century of Male Relationships in Everyday American Photography by John Ibson

Photos sources: Picturing Men and Flickr