Radical Democracy: Since you started doing environmental work many years ago, the context for your work — the climate itself — has been changing drastically. How has that impacted the scope and strategy of your work?

“Stopping the climate crisis is impossible to strategize, because stopping it is impossible. But navigating the climate crisis to a place of stability and the new way of life it will demand — that’s not only easy for me to imagine, it’s easy to get excited about envisioning it.”

Joshua Kahn Russell: I’ve spent the last twelve years with my face deep in the science of the apocalypse, including working on an international level at the U.N. with scientists who are talking about the basic survival of our species. It can be overwhelming.

We live in a time of denial about the crisis, but also coming out of a cultural amnesia in regards to social movements and how change can happen. We need to recognize that we stand on the shoulders of our ancestors; there are real lessons to learn from the past. But there is also something fundamentally new about this crisis, which requires real innovation. Both sides of the generational equation — movement veterans who have so much to teach us, and newly radicalized young folks with fresh thinking — are beginning to walk with more humility to reflect together to face this challenge.

RD: And as an organizer, activist and facilitator, how has your personal perspective changed in the last few years?

JKR: My perspective has evolved from being mostly based in hard-nosed analysis, to something more organic, more intuitive. It’s now about figuring out how to build resilient enough movement institutions to navigate increasing, overlapping crises and change on a scale that we haven’t dealt with since the last Ice Age. That’s a much longer view, a species-wide view — deeply influenced by the spiritual cosmologies forged through the struggles of Indigenous peoples in North America, in particular.

The world is changing faster than humans are accustomed to dealing with. We have evolved to live in relatively stable circumstances, but all the systems that support life on this planet are on the brink of collapse or in decay, and being pushed there by political and economic systems that Social Movements have been challenging for a long time. The whole human family is in trouble, and in for a major transition. Our work is to help shape the direction that transition takes.

RD: Last year’s agreement in Paris was the outcome of many years of global dialogue, and in a sense is the “human family’s” official, establishment response to the climate crisis. Some activists say it’s a fraud because there’s nothing compulsory, no punishment for not hitting numbers. Others say it should be celebrated. What’s your take?

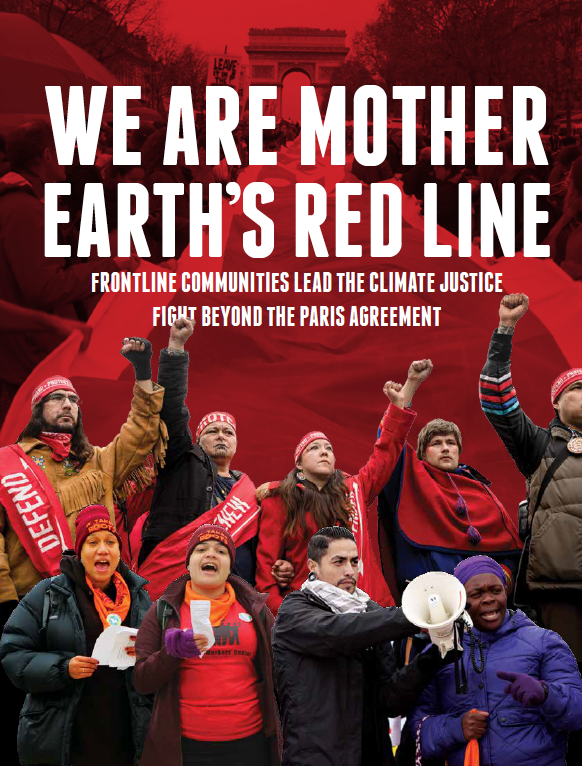

Report on Paris Climate Conference from the Grass Roots Global Justice Alliance.

JKR: I didn’t go to Paris. But of course the answer is both — it should be celebrated as well as critiqued. I spent so many years in these U.N. spaces in Poland, Copenhagen, Barcelona, Thailand, when we were having all these meetings that led up to Paris. I didn’t go to any of the conferences after Rio. I was burnt out, traumatized.

Now I have a lot more curiosity about how these international agreements actually affect us. A really good report was put out by the Grassroots Global Justice Alliance called “Mother Earth’s Red Line,” which they put together with the Indigenous Environmental Network and the Climate Justice Alliance. They talk about their delegation to Paris, and their political breakdown of the outcomes is clear-eyed and useful — they talk about it not being binding, or anywhere close to what we need. That’s true. It’s a strikingly inadequate document.

RD: Is there anything worth celebrating with the agreement?

JKR: Of course! But it depends on what you expect from those institutions, and why you’re engaging them. The Paris agreements are both a big step forward, and nowhere close to where we need to be. If you never expected there to be an international treaty on climate change, the Paris Agreement is a really important moment. Major countries finally admitting that climate change is real, that they’re disproportionately responsible for it, is a big deal.

Many of the early fights were about, in U.N. language, “common but differentiated responsibilities.” If your country developed and industrialized by pouring disproportionate carbon into the atmosphere, then you have a disproportionate responsibility to deal with it. So, the US and Europe have more commitments to make than, say, Tuvalu does. Even just admitting that couldn’t get done until Paris. Winning that acknowledgement from the U.S. is crucial, as a matter of policy. We‘ve been in an extra uphill battle, getting our government to sign international agreements, and figuring out out how to enforce them domestically.

Climate deniers used to say, “China is emitting more carbon right now than the U.S. and not doing shit, and we shouldn’t do anything until they do.” They can’t hide behind that stance anymore. China is investing more in scaling up renewables than anyone else in the world.

RD: Everything, including the politics is shifting. How has the Paris Treaty, and the many years of international meetings leading up to it, changed the movement itself?

JKR: It’s helped people realize the need for international collaboration and solidarity that’s less controlled and guided by international NGOs, and outside of State-controlled forums like the U.N. It was remarkably challenging for Peoples’ movements, especially from the Global South, to engage these arenas because of funding and geography. Still, these movements really schooled the civil society institutions from the Global North and taught us a lot. There are barriers to collaboration outside the Internet that a lot of these international nonprofits hold the gate keys to. That’s been changing as a result of these international meetings. Our movements are maturing

It could sound discouraging to say that one of the most hopeful things about the U.N. process was getting us all together and realizing we don’t need the U.N. to have a process. [laughs] But Paris gives us a leg to stand on in different ways, and we need as much policy infrastructure to build on as we can get. But there are limitations, and I respect the activists who say, “Don’t be duped by this dog-and-pony show. It’s another way for politicians to appear to care and not actually do anything, because long-term problems can’t be fixed by short-term politicians who only care about getting elected.” That’s all true.

RD: Right. Politicians try to appeal to voters demanding action on climate change — without pissing off their corporate sponsors.

JKR: The fossil fuel industry has a stranglehold over our entire electoral system, and that requires an integrated inside-outside strategy from movements, not just faith in the beltway. Thinking Democrats in charge would be more progressive than they are now, or that Hillary was secretly more liberal than she appeared when campaigning — that, I think, is total horseshit.

RD: Do you think it was within reach to sign a better, or tougher agreement? Was this a missed opportunity in that sense?

JKR: I do think the Obama administration would have liked to sign a much tougher agreement. After Copenhagen, I spoke to the lead negotiator on the U.S. team, and they were just as frustrated as we were. They believed climate change is real, and they’re in this position where they know if they make a commitment the country can’t follow through on, that’s actually worse on the international level. Those negotiators, and the Obama administration’s goals, were held hostage by the fossil fuel industry’s control of our “democracy.” But don’t pretend they were willing to fight on that. They had a lens of pragmatism I don’t agree with, based on being held hostage to the politics of business as usual.

For example, the Paris accord sought to cap temperature rise at 2 degrees Celsius — which we’re currently set to sail right past. But even that goal means cooking the continent of Africa. The Association of Small Island States said, “Do you realize that position means our deaths? Our islands will go underwater once we pass 1.5 degrees. Your ‘highly ambitious goal’ is still death for us.”

RD: That’s a pretty serious clash of perspective.

Protest installation in Paris during the 2015 UN Climate Change Conference. When a public march was cancelled due to security concerns, protestors improvised and placed thousands of pairs of shoes at Place de la Republique to stand in for their owners.

JKR: The problem with these debates is that most people are right. We live in a time full of contradictions. We need to build a movement that learns not just to walk contradictions with nuance and humility, but to actually understand in a cultural sense that the world we are in is defined by contradictions, as are those of us trying to make change while living in this system.

RD: So you think we need to embrace, or at least learn to deal with, those inherent contradictions to move forward?

JKR: Yes. We need movements that learn to love contradiction as a source of creative inspiration and openness.

The U.S. Left has historically been all about debating who has the right line. I’m not saying we’re all in the same tent, or that all the contradictions are healthy. But in a context of chronic escalating crises we need to learn how our shifting terrain gives us opportunities to build more, be more visionary and creative — and to give ourselves permission to be imperfect, because in many ways we still embody the systems we’re fighting.

“The way humans have built this global culture, where white supremacy, capitalism and patriarchy are constraining us, I think it takes a species-wide moment at the brink of extinction to hit the shift button. I’m not afraid of that.”

It’s the spiritual work of our generation, of our movements, to embrace those contradictions in a way that we are repairing our own toxicity, healing from what we’ve done to ourselves.

The only way to heal is to acknowledge that reality is much more complex than rational minds can perceive. What appears to be a political contradiction to a rational mind, if you add a spiritual lens, is not a contradiction at all. The way I was taught to live by the Left — thinking entirely rationally — meant that I would focus on the contradictions as a problem to be resolved.

What I’ve learned since, is that you don’t need to fix those contradictions if you have this other state of being and awareness. This approach is a gift to us from movements all over the global South, and the global North — primarily Indigenous movements and new Black movements. If you’re thinking only rationally, you’re picking the wrong fights. We pick fights with each other that make us smaller instead of bigger. I think we would pick different fights if we embraced our contradictions as a source of wisdom.

RD: Are you hopeful that we can build that Movement capable of embracing our contradictions? That we can make the necessary shift of perspective?

People’s Climate March, 2014. Photo by Joe Brusky.

JKR: It’s already happening. The evolution of our movements in recent years is remarkable! I’m learning so much.

I believe that we are already on a path towards that type of movement, and, by way of contradiction, also on a path towards extinction at the same time. Perhaps we need to actually be on a path towards extinction in order to get to where we can shift perspective. The way humans have built this global culture, where the sicknesses of White Supremacy, Capitalism and Patriarchy so deeply plague us, I do think it takes a species-wide moment at the brink of extinction to hit the shift button. I’m not afraid of that.

I can be hopeful because I accept that a lot of us are going to die. Saying that out of context is a remarkably ugly thing, but we need to acknowledge this reality with compassion, not cynicism. A jaded person may say this as a way to justify inaction, because it’s basically being “comfortable” with people less powerful dying on a mass scale.

RD: But you’re clearly not coming from that angle.

JKR: I have the opposite of that perspective, though it may sound similar. There is a white middle-class style of hysteria around the climate, to which many social movements ask “whose world is ending, exactly?” It’s one thing I’ve learned from Native people, and from Black folks who say, “Our people are already dying, and have been dying for a long time.” The genocidal consequences of the systems of extraction are just expanding. The perception that this is completely uncharted territory, on one level, is just a white thing. Which is why communities who have been forced to navigate fucked-up, oppressive, circumstances for so long have so many insights for how to survive. The only response is to take care of each other.

“In this moment of crisis all over the world, one of the great pains I hear echoing, no matter where or what perspective it’s from, has to do with humans having a collective consciousness. We have a sense of togetherness, but the ideologies of individualism, capitalism, and white supremacy teach people to be removed from that.”

Oppressed communities are much more realistic about what’s coming, and understand that no matter what, it’s going to be a rough ride. That’s nothing new for oppressed people. What is new is that it’s going to include everybody to some degree. There’s a spiritual aspect to finally accepting that. I spent my first twelve years of climate change work fighting that truth, having a complex relationship to what we call “catastrophism”. The politics of apocalypse are in itself complex, and rooted throughout human history in different ways. But in the end, it means recognizing that we’re part of a shift that will last generations. It’s so much bigger than us. But we all have a role to play.

It’s like the famous Jewish quotation “It is not your responsibility to finish the work of perfecting the world, but you are not free to desist from it either.”

RD: It sounds like you’ve significantly shifted what you’re fighting, and fighting for.

JKR: I realized my despair was primarily rooted in my inability to grasp what mass death — in my lifetime — means. That’s what was making me despair, making me have an individualized response of putting the weight of the world on my own shoulders. But even if we cut off point-source pollution tomorrow, we would still have thirty years of aggressive climate change coming down the pipeline, because of the feedback loops we’ve already triggered. Reconciling that reality with hope used to be a contradiction to me, but I’ve learned to accept that we are on the brink of a species-wide evolution. Which is actually much stronger fuel for me to persist with the work.

RD: So, what do you see as possible results of this evolution, and what has to happen for it turn out well for humans?

JKR: We’ll need to learn how to live in balance with each other and natural systems again. We don’t have a choice anymore. I do think no matter what happens next, it is part of our evolution.

Several outcomes are plausible to me. One is that we kill ourselves. We’re getting a chance to overthrow this system, and if we don’t do that, then maybe human life wasn’t meant to grow in the way we assumed.

The second possibility is that we’re going to “win”, to some degree. This means accepting that the climate crisis is happening, and that crisis will bring out the best of us, as well as the worst. Whether or not there’s justice on the other side, that becomes our work. That’s work I can wrap my head around.

Stopping the climate crisis is impossible to strategize, because stopping it is impossible. But navigating the climate crisis to a place of stability and the new way of life it will demand — that’s not only easy for me to imagine, it’s easy to get excited about envisioning it.

The third possible outcome is the frightening one. I don’t breathe much life into it because there’s no agency in it. It’s the possibility is that a lot of people are going to die, and the rich people with all the resources will find a way to make a little safe bubble for themselves, and they’ll suck the planet dry of resources. By then, technology will have gotten us into space, and they will move beyond this planet with the same extractive mindset — basically realizing science fiction’s fears of human beings as parasites. That way isn’t actionable, so it’s not worth giving any energy to…but it would be dishonest to say I don’t occasionally feel overwhelmed by its plausibility.

RD: It sounds like we’re going to have some serious shit to deal with, no matter what happens at this point. That realization seems to be opening people up to new politics, new actions, new ideologies…

JKR: A political ideology is only as good as the actions it produces. So we have to find a deeper consciousness — and this is another contradiction — on one hand accepting, on a cosmic level, that we are going to go through a period of intense trauma, death, and loss. To steel ourselves for that, and not let it kill our souls, we have to stay in tune with that pain in a present enough way that we make choices based on the urgency and unacceptability of that death, even as we are accepting it in the big picture. That’s the kind of contradiction I’m thinking about. I don’t really have the “movement language” to talk about it yet, but that’s my best articulation at the moment.

RD: Right. We haven’t figured out how to talk coherently about a catastrophe like this, yet.

JKR: Almost every way I have to talk about it makes me sound either like a woo-woo hippie, or like I’m approving of death or cheerleading the apocalypse. In fact, the deficiencies of those perspectives are what led to me to this perspective, and the only way to understand it is to embrace the contradictions as both true.

In this moment of crisis all over the world, one of the great pains I hear echoing, no matter where or what perspective it’s from, has to do with humans having a collective consciousness. We have a sense of togetherness, but the ideologies of individualism, capitalism, and white supremacy teach people to be removed from that.

The absence of that connection is the spiritual crisis that I think defines our time. It’s a spiritual crisis that secular, capitalist culture — shaped by white supremacy and patriarchy — has zero answers for.

RD: I can’t help but think of Standing Rock. It brought attention to the DAPL issue, of course, and indigenous rights in general, but it was also the first, big public expression of this current movement of movements. I know there were delegations from various groups in the Movement for Black Lives, from environmentalists, obviously, as well as delegations from Palestine… It brought a perspective of solidarity, as well as a powerful spiritual element.

JKR: I wasn’t there, but like everybody else, I was really changed by the courage of the Water Protectors, the fulfillment of the prophecy of many tribes coming together, and of healing.

The Water Protectors brought an Indigenous cosmology, as a way to take the fight to the spiritual plane, to broader movements. We talked earlier about how the world is changing faster than most humans can keep up with, and it’s disorienting to lots of people. Unless our movements are able to offer people spiritual grounding to understand the nature of the transition we’re in, and not just a science-based analysis, I’m not sure that we’re going to be successful.

Spiritual movements have had the power to catalyze change on a scale and pace that is unlike anything else, and they also reveal truth: the truth that we are all one, all interconnected, and that the ingredients of life are sacred and precious.

But we can’t jump to unity without dealing with the reality of living in a world with all these systems that are designed to divide us. The spiritual truth of our interdependence and collectivity needs to be reconciled with the material truth that we’re not all one, and that in this world, with these systems that govern our lives, our differences are really important. How to navigate these contradictions is one of the things that I think Standing Rock has taught many social movements, and it’s something that continues to lift me up.

RD: I think that message of oneness, of deep solidarity despite our material differences, has helped coalesce our movement of movements in an important way. Having a common enemy in Trump has also helped united movements.

JKR: Trump represents a dying paradigm that’s on it’s way out. It’s a thrashing, dying beast, and a dying beast can do a lot of damage. Trump has already done significant damage, and so the question now is how much more damage is done before we move into a new era, what kind of struggle is necessary to bring that new era about.

In terms of making changes within existing systems, the landscape has completely changed. A lot of my work on the Keystone XL Pipeline, and a lot of other work that was done in the last eight years, was undone with the stroke of a pen, at least in terms of policy outcomes. Fighting Trump is going to look very different than what we’ve been doing.

RD: Trump’s been doing real damage from within the system, but it feels like there’s a new opportunity for us to work on the inside, too.

JKR: Bernie really created an opening to re-imagine the electoral arena for progressives, which a lot of us had given up on. I think the fights that are happening for the soul of the Democratic Party are really important — and a few years ago I certainly didn’t think that way. Right now, Sanders is by far the most popular politician in the entire country, and the more that the establishment media and establishment Democrats continue to marginalize and demonize him, the more popular he’s going to get. They don’t seem to understand that.

RD: It’s ridiculous. The Democratic Party seems unable to react to the Bernie movement or to Trump. It’s like they’re hoping it all just goes away, and they’ll be the only ones left standing.

JKR: Part of the liberal reaction to Trump is the “this is not normal” narrative — but most Trump supporters are thinking, “We hate normal. That’s the whole point.” That’s where we can agree — what was considered “normal” was a neoliberal march off a cliff. This creates an opening to push for real solutions, instead of Trump’s racist snake oil.

It would be one thing if Trump was just a fascist, but he’s also remarkably incompetent and makes choices based on his own ego rather than any other factor. It’s hard for me to imagine a future where Trump doesn’t go down as the least popular president in history, and go down in a dramatic way. That will create an opening, because with Trump’s scorched earth policy we’re going to have to rebuild so much. He’s destroying EPA, he’s destroying HUD, he’s destroying so many of the arms of government that actually help people. We’re going to remake those institutions in a much deeper, more thorough way than if we were just tinkering around with the existing trajectory of neoliberalism.

When Trump issued an executive order banning travel from several Muslim countries, activists quickly organized protests at airports around the country, including JFK International Airport in NYC, pictured here.

RD: Right. And outside the system, there’s been an explosion of organizing and protest — the Women’s March, the Muslim travel ban protests, the Science March and upcoming Climate March…

JKR: Yes. An entire new generation of people has broken though the cultural inoculation against protest, and we’re seeing more democracy in the streets than I’ve seen in my lifetime, ever.

But I think we need to understand civil resistance differently. It needs to be about power, not persuasion. The upcoming Climate March is a strategy that was developed to pressure and persuade Hillary Clinton — but nobody really thinks that getting those people into the streets is going to influence Trump’s decision making. That’s not a reasonable goal, so it becomes even more important to articulate the other goals, the other reasons to march. Like building a strong, mobilized base that can help shift the balance of forces in this country when the other shoe drops on the Trump administration, that is a goal. And that’s something the climate march will help to build.

RD: It feels like what was once the most powerful argument used against progressives and radicals, the argument that things simply can’t be changed very much, has collapsed. Once people realize that we can change things, everything changes. People have a sense of agency again — as that shift from persuasion to movement power indicates.

JKR: Exactly. It’s the neoliberal argument that change can’t happen in a systemic or dramatic way, but only in a slow, plodding, linear way that requires a certain calculus of pragmatism — and that being in the streets has no purpose or consequence. All of those assumptions have been upended.

This all gives me hope for what we really need — not just more protest, but a fundamental revitalization of our democracy, and the understanding that voting is only the most superficial version of it. I think that there’s a new kind of spiritually oriented, holistic, integrative activism that is emerging, and continuing to build it is more than ever our task.