But I wasn’t hanging out in the mall, smoking in the park, or chilling round the block with my mates. No. I was in the library.

I was a vociferous reader. I read everything I could find: on philosophy, politics, religion, spirituality.

And I wrote to keep track of what I was reading. Voluminous notes. Some of these spawned further reflections, and led to tangential writing projects.

I was on a mission.

For whatever reason — troubles at home, teenage angst — I felt a burning need to make sense of life. And conventional education in school didn’t seem to cut it.

Dissonance

Waiting 1

I’m not sure what set me on this course of curiosity and discovery.

I know I had a sense of confusion and alienation about the way the world works from a very young age.

My earliest memory of this was my emotional response to TV adverts by charities trying to raise money for poor people in Africa. I think I was about eight or nine.

I remember the internal tension of cognitive dissonance. Why were so many people in Africa living in such dire extremes of poverty, while we were living in relative comfort?

My axiomatic sense was that this situation was just plain wrong. The children shown starving on TV, half naked with bellies inflated from malnutrition, hadn’t done anything wrong, could not have done something to deserve being born into such conditions.

Yet for some strange reason, no one around me really seemed to find the situation all that unacceptable. They lamented it, but it wasn’t something that particularly troubled them. And this tacit acceptance of the inevitability of injustice troubled me more.

I remember deciding while staring at the TV that when I grew up I’d do something about it.

Another episode of awakening was the genocide in Srebrenica, Bosnia. I was around 17. I had been watching the news of the war quietly for the last few years.

None of my peers seemed too bothered. I remember finally speaking about it, hesitantly, over the phone to my best friend. I explained how crazy it was that the UN was doing nothing to help these besieged families. What kind of world were we living in? Wasn’t there something we could do?

“Well, you’re right, but I kind of feel that right now we shouldn’t really be worrying about stuff like that,” she told me. “We should be having fun.”

My mouth was agape, but I had nothing to say. Maybe it was my Muslim identity that made the Bosnian war seem closer to home for me than so many of my friends.

Either way, the sense of dissonance was growing.

Later that year, we went on a family trip to Bangladesh, visiting the capital, Dhaka, and the village of Cilete. I had visited before, but going as an adolescent came as a shock. I saw firsthand the reality of devastating poverty.

Hundreds, thousands of children, roaming around broken, muddy roads, amidst shit and rubbish. Of course, there were adults too, but mostly I remember the kids. I remember them coming up to me when we were shopping for jewellery and clothes.

I remember the casual callousness with which they were treated when they came up to us, begging in desperation — a flick of the hand, to remove the pesky pests from soiling the vicinity. Their poverty, and their sheer numbers, had made them ‘Other’ — beyond saving, beyond compassion. Irrelevant.

Many years later, these memories would come back to haunt me when I found out that my uncle, Aftab, a leading political science professor and activist in Dhaka, was shot dead in the face at point blank range by a gunman who had broken into his flat.

The murder was merely one in a string of assassinations of teachers and activists that had wracked the country at the time. Shortly after, my young niece, whom I’d never really had a chance to know, died of a degenerative disease. My aunt had sunk into depression. She, too, died shortly after.

I remember them fondly. When I was just a boy of around 4 or 5, we used to live with them in our first home in Gants Hill. They used to babysit me. Now, there is barely a trace of them, except perhaps in my dim memories, and my uncle’s writings.

These episodes coalesced and increased my determination to understand how these grotesque extremes of wealth and poverty, violence and calm, could co-exist in one world, and to change it.

Of course, there was the context that when I was quite young my father had been made redundant from the large accountancy firm he’d worked for, due to corporate downsizing. The job loss had wrought a massive dislocation inside our relatively well-off middle class family.

We remained relatively well-off, but not without trauma. My dad had become depressed and was unemployed for a long time before he managed to get back on his feet. He started his own practice and at various points won smaller roles at smaller companies, but never earned at the levels he had before.

The financial impact and the new demands on my mum, who went on to work as an English teacher in a school in Tower Hamlets, turned their quietly strained marriage into an everyday apocalypse of a relationship. My mum and dad are first generation Bangladeshis, and the marriage had been arranged in a highly traditional fashion (my mum hadn’t even seen my dad before they were married off), so things weren’t exactly a bed of roses from day one.

The stresses and strains of keeping up with the Joneses led the situation at home to deteriorate to what felt like unbearable levels.

Death

Beneath a shell

Then my dad had a simultaneous heart attack and stroke.

My parents were arguing in the lounge, as usual. The screaming reached a crescendo before my dad was suddenly up with his back against the wall, unexpectedly silent, clutching his chest. He slid to the floor.

In the hours that followed, I was confronted with the spectre of death.

Death didn’t come for my father that day. Instead, he lost the ability to speak, to write, to type. He could barely walk. It took him years to recover. My mum kept the family afloat during these extraordinarily difficult times.

A few years later, my dad relearned through painstaking struggle how to talk, write and type, though he was never the same. He restarted his ailing business. He struggled to win back the clients who had inevitably gone elsewhere, with only a loyal handful returning.

Then, out of the blue, death came for my best friend. She died suddenly of a rare blood disease. Although I’d known she was ill, her death came as a total shock. I suppose, for me, it was a sort of ‘last straw’ moment that ripped open a hole in my world, and led me to question everything — my faith, my family, my future.

I’d become thoroughly disillusioned with life. School wasn’t teaching me anything about why things were the way they were. I wasn’t learning anything about who I was, and what life is even about; about what we’re doing on this planet; and what we ought to be doing before we die. I wasn’t learning anything about death. I wasn’t learning anything about life and death.

As far as I was concerned, I was being spoonfed utterly irrelevant bullshit by an education system that functioned in service to a broken system blind to its own flaws: a system that tolerated the mass impoverishment and mass murders of innocents as a regrettable but largely inevitable ‘fact-of-life’, which could perhaps be occasionally alleviated through bizarre celebrations held by society’s most wealthy, through things like ‘Band Aid’ and ‘Red Nose Day’; a system that had no answers as to the mystery of life and its inevitable destination.

Exile

Exiled

I experienced a deep sense of urgency. Death proved that life was, indeed, sacred. We had such little time on this blue dot amidst an unimaginably vast cosmos to truly learn about life itself.

And so I’d begun retreating from my own friends as I embarked on a private journey to understand life, death, the world, and my place in it.

The roots of my approach to journalism can be found here, in the notes and questions and lines of inquiry I opened up for myself in Ilford library.

As I stumbled from one crisis to the next — failing my A-Levels, resitting my A-Levels, dabbling with a foundation course in Art & Design — whenever I could find a moment, I was writing.

Writing to make sense of the world, to make sense of life and death, where answers were not easily visible. Writing to translate my search for answers into something tangible in the real-world, where such thoughts, ideas, visions were barely tolerated.

In this period, I wrote the drafts of three books on politics, philosophy and spirituality. I’ve never published these, and wouldn’t do so now without significant revisions. But these tomes were the foundation of the open inquiry I had begun.

My writing was my freedom.

It freed me from the limits and constraints around me. It opened new horizons. It anchored me in a sense of deep connection to what I began to realise is all that really matters: by its very transcience, the beautiful sacredness of the web of life on Planet Earth, and the interconnectedness of all life.

Set against this emerging vision, was the game of endless extraction taking place in the world, placing humanity on a collision course with the natural world, and undermining our very own planetary life-support systems.

In his seminal To Have or To Be?, social psychologist Erich Fromm showed that modern industrial civilisation is largely characterised by a particular “mode of orientation”: “having.”

It is a mode of human existence associated with a particular view of the self and the world, and a set of ideas and values for self-maximisation — “happiness”— defined by maximising one’s ownership of things, people, resources, and even experiences or particular sensations or feelings.

Yet this mode of orientation is associated with the acceleration of unhappiness, epidemics of depression and mental illness, rising inequalities, social polarisation and environmental destruction.

In contrast, Fromm pointed to a mode of orientation known as “being”, expressed frequently in the world’s wisdom traditions: this mode of existence entails an “aliveness and authentic relatedness to the world”; a view of the self and the world not as set apart, thus requiring the former to extract endlessly from the latter, but set together, implying a mutuality and interconnectedness.

The mode of “being” thus opens up a new horizon: that of recognising and living by “the true nature, the true reality” of both the self and the world.

What Fromm saw is that the structural dysfunctions of our societies are not just problems ‘out there’. They are, in a way we still struggle to see, ‘in here’ — embedded embryonically in our own modes of orientation, in you, in me.

And thus, I had begun to understand, just barely, J. Krishnamurti’s powerful teaching that no meaningful change in the world is possible without changing who we are:

“What you are, the world is. So your problem is the world’s problem… In our relationship with the one or the many we seem somehow to overlook this point all the time. We want to bring about alteration through a system or through a revolution in ideas or values based on a system, forgetting that it is you and I who create society, who bring about confusion or order by the way in which we live. So we must begin near, that is we must concern ourselves with our daily existence, with our daily thoughts and feelings and actions which are revealed in the manner of earning our livelihood and in our relationship with ideas or beliefs… How to bring about a fundamental, a radical transformation in society, is our problem; and this transformation of the outer cannot take place without inner revolution.”

These ideas were what grounded all my writing. And they informed the structure of my entire journey of open inquiry. I saw my task as a writer as simple: to move from deconstructing the failures of the system in its current form, into exploring the possibilities for new, better systems.

Return

Regeneration

Eventually, I began taking my open inquiry into the public domain. I started doing investigative writing for various online magazines and organisations. Sometimes I drew on the research I’d already done to produce heavily-footnoted critiques of US and British foreign policy; other times I was producing country reports on human rights practices.

My writing focused on exposing what Fromm described as the mode of “having” — the paradigm of endless extraction, and its manifestation in military expansionism and economic plunder.

Then the Twin Towers came crashing down, and the world changed forever. I felt myself pulled into trying to understand how and why this could happen.

Once again, I wrote to make sense of the terror attacks, their context, and their aftermath, for myself. But before long, I had reams of pages. These writings culminated in my first published book, The War on Freedom: How & Why America was Attacked, September 11, 2001.

This turned out to be the first book to critically investigate the Bush administration’s official narrative around the attacks, and perhaps the only to do so without putting forward any single alternative conspiracy theory of what had happened. The book was based on public record sources, and conducted exclusive interviews with key people like David Schippers, the former US House Judiciary Committee’s Chief Investigative Counsel for the Clinton impeachment.

Schippers had told me about a cohort of FBI Special Agents who had come to him months before, warning of an imminent attack on the financial district of lower Manhattan – and sounding the alarm that their investigations had been inexplicably blocked from Washington.

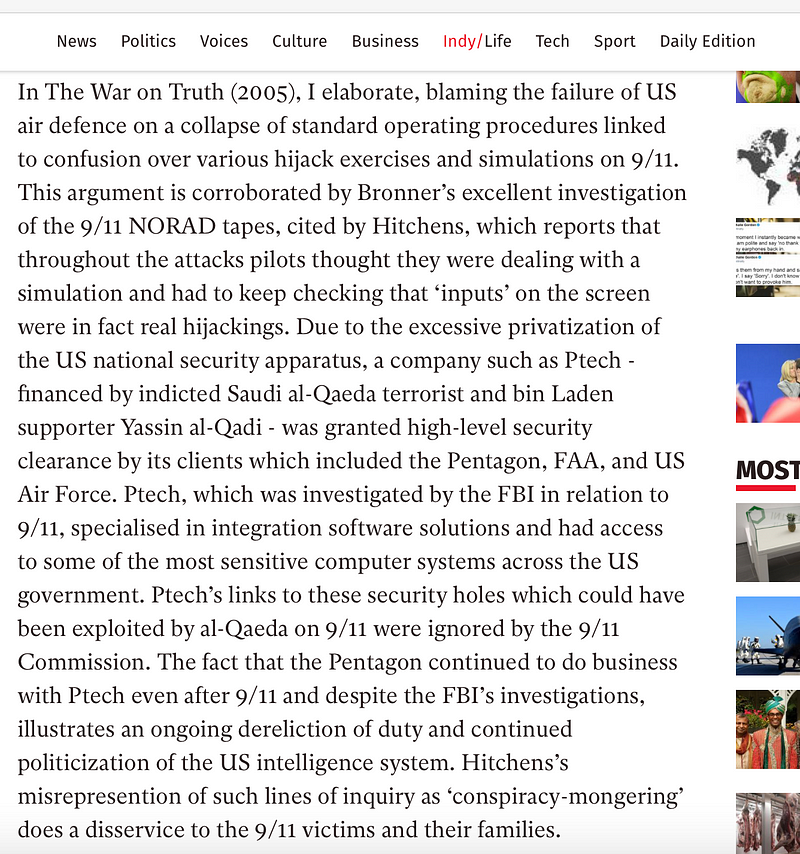

The late American legend, Gore Vidal, took up my book and wrote about it in a lengthy feature essay in The Observer. That’s a story in itself — it led to my bizarre spat eight years later with the late Christopher Hitchens in the pages of Vanity Fair, culminating in my response to Hitchens published by The Independent on Sunday.

Hitchens painted Gore and I as loony conspiracy theorists. But he had failed, as had the 9/11 truth movement, to grasp our point.

The experience with Hitchens was instructive. On the one hand, I found myself lambasted by neoconservative sympathisers as a ‘conspiraloon’. I was accused of advocating an ‘inside job’.

On the other, many in the self-styled ‘truth’ movement had decided that I was some sort of ‘shill’ offering a ‘limited hangout’ — a version of events that might by partly true but didn’t go far enough in claiming the US government “pre-arranged” the 9/11 attacks.

What neither side was able to grasp is that the reality of what happened on 9/11 is complex. ‘Occam’s razor’ is not up to scratch to capture the murky complexity of the intersecting black operations, policy failures, deliberate decisions and planned strategies that converged to culminate in the 9/11 attacks.

My role as a journalist was to open up lines of inquiry, not to force particular theories down anyone’s throat.

As I ended up explaining at length in The Independent on Sunday, the lines of inquiry challenging the 9/11 official narrative neither confirmed nor negated any specific conspiracy theory. If you wanted to, you could work through the facts to make them fit your pet theory.

What the facts did strongly suggest is that the US government had maintained geopolitical alliances with known state-sponsors of Islamist terrorism, key Muslim dictatorships – like Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, Pakistan and Turkey – which were so institutionally protected by the US national security system, they had begun to compromise it entirely.

Those alliances, often but not always motivated by the goal of controlling the Muslim world’s vast oil resources, were frequently enmeshed with clandestine support to Islamist militant groups as a strategic force to counter Russian and Chinese influence in Central Asia and Eastern Europe.

On 9/11, these deeply embedded alliances and their detrimental impacts on the US national security system played a fundamental, and officially unacknowledged role, in hampering the intelligence community and the wider national security system.

The stakeholders that understood and appreciated my approach the most were people who had been directly affected by the attacks. For me, this was the litmus test. They asked hard questions. They demanded transparent answers. And they didn’t pretend to know ‘the truth.’

My book was read by several members of the 9/11 Family Steering Committee, specifically the ‘Jersey Girls’, the brave, relentless widows who had lost their husbands in the attacks. Many of my lines of inquiry fed directly into the probing list of questions the Family Steering Committee put to the 9/11 Commission as part of its investigative mandate. In turn, my book became part of the official 9/11 Commission Special Collection – the 99 books officially provided to each 9/11 Commissioner to use in their investigations.

And so now, here I was — a published author and investigative writer. I had never really expected this to happen. But at this point things got real.

Getting married and having my first child were instrumental in me realising that if I was really going to do this, I needed to get training. I had a responsibility to my readers, and to my family.

So I went back into education. I ended up at the University of Sussex in Brighton, where I embarked on a Masters in War and Peace Studies in the Department of International Relations.

Training

Waiting II

Over the next few years, as I transitioned into a PhD on the intersections between colonisation, empire and genocide, the primary driver of my journalism was crisis after crisis in the world.

That, of course, is the predicament for most journalists. We end up being caught in the news cycle, like rats in a treadmill, producing copy to deadline within a fixed editorial format with little scope for deep inquiry.

But I didn’t work for a traditional media institution. I was studying and teaching at university — an entirely different environment, where I had time and resources to do serious research that could culminate in longform work.

I saw my task as being to offer a corrective to narrow, myopic and often self-serving reporting by traditional media institutions.

In this period, my journalism extended into three primary directions, all reactions to major global disruptions: a deeper investigation of the events that led to 9/11; the reality of the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq; and the terrorist attack on London on 7th July 2005.

When the Bush administration began agitating after 9/11 to organise a coalition of the willing into invading and occupying Iraq, it hadn’t come as a surprise. I’d already published two extensive investigations online in October 2001 cataloguing decades of US and British warmongering in the beleaguered country, including the genocidal impact of the UN sanctions regime and the constant efforts to disrupt the UN weapons inspection process.

After the invasion, I pulled this material together to make my second book, Behind the War on Terror: Western Secret Strategy and the Struggle for Iraq.

I did this out of deep frustration with the dire reporting on US and British relations with Iraq. There was no context, no history, no grasp of the geopolitics, and no acknowledgement that we may have certain vested interests; and barely any acknowledgement that Saddam Hussein, the evil creature we were dealing with, was a direct result of a series of US and British policy interventions to support the rise of the Ba’athists in Iraq.

While myopic journalists were writing about the Saddam’s alleged obstructions of the UN weapons inspection process, Saddam’s horrific evils against his own population, and the unprecedented danger his regime posed to the entire world, I saw my task as illuminating that complexity and history so few were talking about. How did we really get here? Who gave Saddam his WMD? Did he still have it? And what did that tell us about what we really needed to do to solve the Iraq crisis?

Behind the War on Terror contextualised the war against the long history of US and British meddling in the Middle East. The Iraq crisis was the legacy of a century long process of imperialist interference, motivated to control the country’s vast oil and gas resources.

I also drew on UN and other public record documents showing that Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction (WMD) had long ago been destroyed — and that the entire weapons inspection and intelligence process was being manipulated, quite deliberately, to orchestrate the drive to war.

At the time, this sort of argument was beyond the pale. There was a stark disconnect between these findings, and the chorus of slavish reporting across the mainstream media, which had rallied around the official government line.

Shortly before the war, I attended a lecture at the University of London by Hussain al-Shahristani, a former Iraqi nuclear scientist who went on to hold several ministerial positions in various postwar Iraqi governments. He is now Iraq’s minister of higher education.

Al-Shahristani was among those in the expatriate UK Iraqi community who unashamedly agitated for war, and went on to personally reap the benefits afterwards.

His speech was full of shit.

He had put together a list of Saddam’s alleged nuclear, chemical and biological weapons programmes. He openly demanded the need for an invasion to save the Free World from imminent doom.

Of course, I had been collating public record data from sources much more knowledgable than me, proving that these had, in fact, been thoroughly dismantled in the 1990s.

When I stood up during the Q&A and challenged Shahristani’s narrative, he ridiculed me, and the room rippled with laughter. Who was this young, dumb upstart daring to challenge an Iraqi nuclear scientist who had been imprisoned by Saddam himself? Shahristani pointed proudly at mainstream newspapers, The Times in London and the New York Times, which backed up his claims.

But the war came home on 7/7, when four British Muslims from London, citing the Iraq War as a justification, targeted the London transport system in the worst attack on the UK since the Second World War.

As I began to dig, I discovered that many of the same geopolitical and intelligence patterns which surfaced in the run-up to 9/11 had re-occurred in relation to 7/7: especially, that alliances with Islamist militants abroad had undermined security at home.

By then, the 9/11 Commission had produced new information that was extremely valuable. It showed that some of what had been reported after 9/11 was incorrect. I realised that I had overreached in my first book, and needed a more systematic approach to navigate the sheer complexity and volume of the available information across geopolitics, foreign policy, national security and intelligence.

But the 9/11 Commission was also seen as an affront among a significant number of 9/11 family members, who had watched as several critical lines of inquiry — especially into US relationships with terror-sponsoring allies like Saudi Arabia and Pakistan — were being shut down.

Similar concerns were surfacing over the 7/7 attacks, as I found out when Oury Clark Solicitors asked me to advise them in relation to their work for the 7/7 Inquiry Group, a group of survivors who wanted an independent public inquiry into the attacks.

These lines of inquiry led me to produce two more book-length journalistic investigations: The War on Truth: 9/11, Disinformation and the Anatomy of Terrorism, a sequel and upgrade to my first book incorporating new evidence brought to light from the two public inquiries into the attacks; and The London Bombings: An Independent Inquiry, which examined British national security policies at home and abroad in the run up to the 7th July bombings.

The War on Truth was a better, more nuanced book. It incorporated critical new information, and corrected errors I’d made in the first book. The conclusions were as conservative as they could possibly be in relation to the facts being documented. No speculation, no theory, no agenda. Just analysis to augment a deeper inquiry that might generate real insights into the collapse of the national security system on 9/11.

Back in London, I launched The London Bombings in the House of Lords with support from 7/7 survivors Rachel North and John Tulloch. The book managed to pick up some — though quite limited — media attention, including positive coverage in the Sunday Times (Bryan Appleyard), The Independent (Francis Elliott and Sophie Goodchild), and feature interviews on Sky News and Channel 4.

Most importantly, The London Bombings was the basis of my special reportsponsored by the human rights law firm, Garden Court Chambers, into police and intelligence counter-terrorism failures. That report later became mandatory reading for all legal counsel for the 7/7 Coroner’s Inquest.

Binaries

Inner and outer

The point here is simple. I had never seen my role as a journalist as that of a mere ‘passive observer’ who simply ‘covers’ what ought to now be categorised as ‘the news.’ I saw myself as an advocate.

My journalism was not about exposing power and then going away to expose more power. It was about empowering the public to demand accountability that might result in real change to our compromised national security institutions.

Journalism that simply ‘reports’ in parrot-fashion what is happening has a function of sorts, but in the cases of 9/11 and 7/7, the victims, family members and survivors of these devastating terrorist attacks had been tripled-failed.

They had been failed by the governments whose national security complexes were deeply culpable in the sequence of events that culminated in terror strikes on the homeland.

They had been failed by official state-sanctioned inquiries which neglected key questions about longstanding intelligence liaisons with Islamist militant groups for geopolitical purposes.

And they had been failed by traditional media institutions which had largely dropped the ball on these questions.

In much the same way that I encountered ridicule for voicing my views on Iraq, responses to my work on 9/11 and 7/7 can be highly polarised. I’m either a politically correct ‘shill’, to those who feel my lack of commitment to endorsing a specific ‘inside job’ theory makes me a traitor to their precious movement; or I’m a ‘troofer’ to those who feel challenging the official narratives of these attacks automatically implies I believe they were organised by ‘the government.’

This is symptomatic of a fundamental problem. It’s long been known that human beings can be cognitively biased.

We gravitate toward information that fits our already existing preconceptions, and suppress or reject information that contradicts them. We dislike uncertainty, especially the uncertainty of cognitive dissonance; so when faced with contradiction and complexity, we often seek to collapse ideas that seem to be in tension with each other into more simplistic worldviews.

Most contemporary journalism tends to reinforce these tendencies. The result is that the scope for open inquiry is muted. Instead we are left with pathologically meaningless binaries. Either Bush did 9/11, or it was sheer incompetence. Either Muslims blew up the London Underground, or Blair arranged it.

Such binaries seek to collapse complexity into easy to understand simple narratives that allow us to make sense of the world from an ideological ‘anchor.’

Throughout my work, though, I’ve seen my role as to try and do the very opposite.

I seek to navigate the complexity of the available data, to see patterns, to ask questions, and to explore possible scenarios — but to admit, ultimately, that in many cases the best we can do is unearth insights that give us a mere glimpse of how power is actually operating.

That is why, for instance, Christopher Hitchens was, literally, unable to understand my argument about 9/11.

This is a critical issue. On 9/11, for instance, it is often not understood that standard operating procedures in relation to the US air defence system collapsed. Conspiracy theorists see such things as direct evidence of an engineering of the attacks by the US government. Incompetence theorists see such things as direct evidence of incompetence. Both are wrong and irrelevant. As a result of adopting presupposed views of how the facts necessitate conclusions, both sides close themselves off to the capacity to actually see and navigate critical data points.

An approach based on open inquiry, on the other hand, seeks to explore, without judgement, what is actually happening, without constantly seeking to force the analysis into a single fixed conclusion. Here is an excerpt from my response to Hitchens in The Independent addressing this point:

So here, what I’m doing is precisely avoiding a preemptive jump to final conclusions.

Instead, we not only probe deeper than others, by doing so we open up facts and connections which reveal the operation of a deeply dysfunctional — and fundamentally corrupt — defence procurement system.

We see direct connections between vested interests tied to the Bush administration, which had simultaneous ties to people suspected of terrorist activity.

We also see that we have a basis not for a final and fixed conclusion about what happened — but the need for further, deeper inquiry into this murky nexus of power that compromised the US national security system on 9/11.

We see the value of suspending judgement, and being open to data no matter how uncomfortable.

And we realise that the most plausible scenarios are likely to be far weirder than either ‘conspiracy’ or ‘incompetence’ theorists ever thought.

I managed to publish this analysis in The Independent on Sunday, but that was a fluke. For the most part, traditional media institutions have failed utterly to inform the public about the complex geopolitical relationships between Western states and Islamist militant groups.

The more I studied these relationships, the more it became clear to me that terrorism was the result of the very structure of the global system. And one of the most essential features of that system is our over-dependence on fossil fuels.

Historically, that dependence was constructed through a series of colonial gambits and post-colonial military interventions across the world, especially in Muslim-majority countries in the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia — where most of the oil and gas could be found. Today, the dependence is mediated through maintaining and propping up relationships with repressive regimes.

My work kept showing that key allies — Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, Turkey, Pakistan, Azerbaijan, to name a few — were heavily complicit in direct sponsorship of Islamist militant groups. Sometimes we turned a blind eye to keep things sweet. Other times, we actively colluded in these relationships, encouraging militant group to run riot in strategic regions to weaken our geopolitical competitors, Russia, China, the former Yugoslavia.

The expansion of international Islamist terrorism was, in effect, happening under our noses, incubated by the most fundamental features of the postwar international order.

Systems

Dream sinew

So I increasingly began to see how resources, energy, and the environment are pivotal to the issues I was writing about.

This insight was reinforced by other stories I was working on at the time.

US and British policy planners saw Iraq War 2003 as a rational mechanism to shore-up Anglo-American power against an imminent convergence of multiple global ecological, energy and economic crises.

Such stories pointed to intersections not only between global ecological, energy and economic crises, but between these and the increasingly repressive direction of Western foreign and domestic policies under the ‘war on terror.’ Yet I found little reflection of these intersections in the academy.

There was a chronic, all-pervasive problem throughout the academy: a resistance to crossing disciplinary boundaries, engaging between the social and natural sciences, and integrating empirical/historical research with theory in a way that captures the real complexity of human societies, particularly their interrelationships with wider biophysical environmental and energy systems.

This gaping hole in our knowledge systems prevents us from truly grasping the interconnected dynamics of the global crises increasingly shaping international politics.

It was like our sciences had missed the elephant in the room — we’d become so embroiled in holding up a magnifying glass to take things apart and see how different things in different domains worked, we’d neglected the bigger picture. And so we’ve never developed a way of seeing how these different things fit together as integral parts of wider systems.

And this was reflected in journalism. Multiple beats, largely disconnected, are the lenses through which reporters translate their discoveries to their audiences. As a result, the interconnections are lost, because there is literally no single beat which allows the multiple dimensions of a story to be explored.

In between research and teaching, I wrote my fifth book, A User’s Guide to the Crisis of Civilization: And How to Save It, to address this problem through an academic work. It’s the first peer-reviewed attempt to develop an integrated social science framework capturing the interconnections of crises across climate, energy, food, the economy, the police-state and terrorism.

I had stopped simply ‘reacting’: A User’s Guide was my first serious step toward envisioning solutions.

A User’s Guide argued that a meaningful understanding of any one of these crises required an understanding of their inherent interconnections with one another. The business-as-usual trajectory implied by this diagnosis had stark implications:

- Crises would likely kick in harder and faster than conventional modelling anticipated because each system we were trying to model is in fact inherently interconnected with the other systems.

- A failure to change course could trigger further economic and social crises – and at worst could lead to synchronous failures resulting in cascading collapse processes.

- Either way, it was clear that the era of fossil fuels and the structure of neoliberal finance capitalism would not survive this century.

Yet our governments, corporations and other agencies have remained in denial, preferring to prolong business-as-usual.

As crises accelerate, they have attempted to consolidate the fossil fuel system: becoming more militarised, adopting more intrusive surveillance, and seeking greater powers of control at home and abroad. And they have done so precisely due to their failure to understand the interconnected, systemic nature of these crises, and their origins in prevailing structures of power.

I was also seeing the limitations of my efforts. It was all well working in the comfort of the ivory tower. But what was the point if the wider public had no idea about these insights?

I felt frustrated with the inherent limits of producing an academic work — a necessary requirement, but one that would limit my readership.

How could these ideas be harnessed to reach a wider, general audience, to inspire people to embark on their own journeys of open inquiry, and to realise their tremendous power to become change-makers in their own contexts?

I made a decision that led to a new turning point. I decided to leave the academy.

I was leaving behind the possibility of financial security and an academic career to embark on a great adventure: to explore new ways of communicating to the public.

Stories

Acceleration

I had no money, and I’d quit lecturing. But I was doing talks about A User’s Guide anywhere I could, to small groups of people, university departments, and other avenues.

And I kept writing. The concept of the ‘Crisis of Civilization’ provided a framing for all my work, whether it was foreign policy, the ‘war on terror’, climate change, global energy challenges, or the economy.

But ultimately, the freelance work felt like being on a treadmill. The pay was modest, you often had to write for free — bigger complex stories which required more time and resources rarely generated interest with mainstream media, as opposed to short, sharp op-eds — and you often spent more time pitching than writing; all the while trying to maintain a day job that actually paid the bills.

And despite writing for a myriad of mainstream publications, to get the pieces published meant that the stories inevitably had to be truncated and dislocated. But I carried on.

I was driven by a sense of urgency. If I was remotely correct, if we really did face a ‘Crisis of Civilization’, then this was it. Humanity only had a short window before we would bring on an escalating wave of disasters.

But I didn’t really know what I was doing. I didn’t have a plan. I wasn’t really sure what the next step ought to be. I just knew I had to stop ‘reacting’ and start enrolling people in a conversation about how to move from systemic crisis to systemic transformation.

The answer fell into my lap when I was invited to give a talk about my book at St James Park in London.

The organisers were occupying a piece of derelict land in Kewbridge, on the suburban outskirts of Greater London, where they had set-up a mini eco-village, functioning without money, growing their own food, building their own shelters from sustainable resources, and generally prototyping alternative ways of living.

After my talk, Dean Puckett, a friend who had been living at the Kewbridge Eco-Village and documenting the process on camera, offered to help me out by doing a quick interview at my home to create a short YouTube clip which I could promote.

Dean popped round my flat a few days later. We sat down in my small orange office. I remember feeling self-conscious about the state of my hair as I stared at the camera lens staring back at me. Dean opened A User’s Guide, and looked at me.

“So, er. Why don’t I just go through it chapter by chapter according to the table of contents, and you can just, you know, explain where you’re coming from. I’ll ask you about what these bits mean and we’ll just let it flow?”

I nodded and grinned. “Yeah that sounds cool.”

Neither of us knew that we would emerge nearly five hours later spaced out with the intensity of our conversation.

“I felt like I was doing an accelerated crash course in global crisis politics or something”, Dean would tell me years later.

A few weeks after the interview, Dean called me up.

“Nafeez… I think we’ve got something really special here. I think we could make a feature,” he said.

Dean had begun splicing parts of my interview with funky animations made by artist Lucca Benney, and archival stock footage from American corporate information films made from the 1950s onwards.

We saw the opportunity: this was a chance to make a feature documentary film targeted at young people. We would distill the complexity of the ideas in A User’s Guide through the simplicity of audiovisual story-telling. And we’d take it on tour as a tool to educate and inspire action. Thus was born The Crisis of Civilization.

We made the film on a shoe-string budget, raising £3,000 from crowdfunding. Despite the tiny budget, the film was a riproaring success. We launched at a number of prestigious film festivals, even picking up an accolade from the BAFTA award-winning filmmaker Nick Broomfield. We got a distributor on board and sold the film to various US, UK and European channels.

Once we’d made a success of the film in a ‘mainstream’ sense, we did what we’d been hungry to do from the very beginning: we dropped the film for free online on PirateBay, Vimeo, and YouTube, where it went viral and picked up over a half a million views without a penny of advertising.

We interacted with audiences at grassroots screenings up and down the country. We talked to people about their visions for the future, and how they wanted to take these ideas forward in their own lives in the search for solutions. Basically, we started a conversation.

The Crisis of Civilization worked because we made it from a place of love, sincerity, and determination. We didn’t follow any standard convention of film-making. We didn’t think about clever PR messaging techniques. We weren’t trying to make money out of the project. We weren’t trying super-hard to be hip so we could appeal to our target audience. We just wanted to make a blast of a film that told the story of this unprecedented, historic moment that the human species is now navigating.

The conversations that emerged at every screening taught me something that I’ll never forget: when people are empowered to really see what’s going on, they’re able to start generating solutions themselves. Our film, quite deliberately, didn’t offer a giant manifesto for change. Sure, we set out some key ideas for the kinds of big structural and systemic changes we thought were needed.

But the main theme of both the film and the book was that to move out of crisis into equilibrium, people themselves need to be empowered to produce solutions.

Another project I embarked on as part of this exploration of new mediums was fiction. I wrote a science fiction novel, ZERO POINT, to explore themes I was discovering in my work, and once again communicate them to a wider audience through popular culture. Though it’s published traditionally, I’m now serialising the novel for free on Wattpad.

Why all these experiments?

Because everything that’s wrong with our societies is related to the marginalisation and disempowerment of people. The most fundamental solution of all, was to allow people to engage in a process by which they can themselves begin to examine these systemic problems and explore potential solutions, in dialogue, and through real-world practice.

This was the mission I wanted to take on as a journalist.

Breakthrough

Overdose

I got my chance at a Big Break when I was recruited in early 2013 by The Guardian to join their crack team of what the paper described as “the world’s best new environment bloggers.”

As The Guardian announcement made clear, my blog, Earth insight, was supposed to cover “the geopolitics of environmental crisis and its links to society, energy and economics.”

In terms of my beat, this was my dream gig.

Under the terms of my contract, I could publish straight to The Guardian website immediately. The paper provided us with editorial and technical training, and we operated through simple protocols so that our editors knew what stories we were working on.

Now I had a home at one of the biggest newspaper websites in the world, to do what I’d been wanting to do: communicate to a mass audience through multidimensional stories that used a ‘Crisis of Civilisation’ lens to cover global affairs and the shift to a post-carbon future.

The only downside was the pay. The arrangement operated on a 50–50 advertising revenue share basis, which started off with payments so paltry I remember having a conversation with a fellow Guardian environment blogger as to whether there had been some sort of mistake.

Then I became one of the most popular environment writers, and suddenly my work for The Guardian brought in just enough income that I could kick-back other freelance writing.

At last, I had the freedom to focus on investigating under-reported geopolitical angles on our global environment, energy and economic crises.

It was short lived.

Breakdown

Swallowed

By late 2014, I saw firsthand how an outlet as reputable as The Guardian was capable of indulging in grievous censorship.

I produced a story on how Israeli military operations in Gaza were, according to a past policy paper by the then-Israeli defence minister, partly-motivated by concerns over the control of Gaza’s offshore gas resources.

The day after the story was posted (it, btw, went viral and became the most read piece on the Gaza conflict that year), my editor called me and said that the paper would be permanently cancelling my entire blog, because this post “was not an environment story.”

I’ve elaborated on the details of this experience below.

When I put down the phone, I was in a state of shock. By the end of the day, when it hit me that the new story ideas I was mulling to post on my Guardian blog no longer had a home, I was devastated.

At first, I was desperate to claw my way back into The Guardian. I had been told by my editors that there were no objections to publishing future stories on the same beat — but the old arrangement was over. I’d have to pitch like any other freelancer.

Multiple pitches later — I remember pitching an exclusive story on the new UN Special Rapporteur for Food calling for a radical shift to low-pesticide, organic forms of smallholder agroecology as a way to solve our global industrial food woes, which was simply ignored (though subsequently published by The Ecologist and Yes! Magazine) — I realised that The Guardian’s environment editors were not going to publish me.

It was the end of the road. It felt like I had been on an accelerating upward trajectory, finding my place in the world, only to smash unexpectedly into an invisible ceiling I didn't know existed.

So what was my place in the world? After all this? I had to decide, again, what I really wanted to do. Should I give up journalism? Should I not bother anymore? Should I go back to lecturing?

For months, I found myself stuck in a place between self-doubt, despair and confusion.

After a while, I began getting emails from people asking me why I hadn’t updated my Guardian blog. What was I supposed to tell them?

In this period of estrangement, I felt powerless. I felt weak. I felt useless. But in that darkness, I began to see. I saw that I had been running through life on the basis of a story of my own powerlessness, a story born of my own experience. Powerless as I watched shit happen to my family, in my family, to me.

But it was just a story. A story that was propelling me forward, driven by insecurity and fear and a need to compensate for it in the world. Journalism had become a crux, my ‘strong suit’, my show of power.

The Guardian was the symbol of my power, an affiliation I wore with pride. But what was it, really? A way of sticking it to the man? A way of validating my sense of self-worth? A way of making up for how I really felt deep inside, a frightened little boy, overwhelmed by my surroundings?

But all that was not, is not, who I am. It was a story I was telling myself again and again, by rote, wired into my neurophysiology by the hand of my own experiences, thoughts and emotions growing up.

The moment I saw the story for what it was, a story that I’d been unconsciously telling myself and reliving and overcompensating for everyday, is the moment I woke up. And that was when I knew, I really knew, that now I could truly begin to write my own story – and no longer be held back by my past.

I found the power to step into my future, and to write a new story, without sadness, without resentment, without envy, without anxiety, without fear, without doubt.

I realised that Guardian readers, especially my readers, had a right to know what had happened. And I realised that if The Guardian was no longer going to be a home for my journalism, then I either needed to find a new home, or create one myself.

Fuck it, I decided. And I went public.

The Guardian’s handling of the situation had made my decision almost inevitable. I could either lie to people about why I was no longer writing for The Guardian, or simply tell them what happened.

What was I really in service to? Protecting my new-found identity as a mainstream writer ‘inside’ The Guardian ‘tent’ who had for unfathomable reasons moved on? Or letting go, and truly moving on by simply being honest with my readers.

I knew that doing so could make me a pariah for much of the traditional media — a journalist who publicly shames the editorial decisions of his publication isn’t likely to get new work.

Which meant, very simply, that I needed to commit to exploring new ways of doing journalism, independently, radically, fearlessly, and without being pulled by the strings of advertisers, big money, lobbies, or special interest groups.

Ultimately, The Guardian’s decision to discontinue my blog because I decided to include “Palestine” in the remit of my beat — the geopolitics of environmental crisis — came from a fundamental ideological and structural problem with the newsroom: the inability to navigate complexity.

It goes without saying that the energy geopolitics of the Israel-Palestine conflict are, obviously, just one factor out of many far more entrenched and significant.

But the numerous cases I had been tracking through my Guardian blog — from Ukraine to the Arab Spring and beyond — showed that increasingly, geopolitical chaos was being influenced by these huge, powerful environmental and energy forces, in ways we still barely understood.

The Guardian’s actions were symptomatic of the wider state of our traditional media institutions: an era of digital ad revenue-centric clickbait, tunnel-visioned narrow reporting, converging editorial pressures tied to a news cycle that has become structurally dependent on official sources of government, defence industry and corporate information.

The world needs more than this.

Experiments

Becoming

I wanted to create a space for truly radical, independent journalism that informs and empowers.

That opens up lines of inquiry in a way that is non-dogmatic.

That challenges power through critical engagement.

That also maintains a capacity for self-consciousness and self-critique.

That is not simply obsessed by the bad news but actively seeks to uncover and empower the seeds of positive social transformation and change.

And I wanted to do it in a way that empowers people. It made eminent sense to experiment with crowdfunding. I settled for using Patreon.com to sustain my work.

The crowdfunding experiment has been a success. But it’s not perfect.

The Patreon system provides me a steady source of income from a community to which I’m accountable, and where we have open lines of communication. They commit to a monthly subscription, and they can pay literally anything they want.

The crowdfund allows me to approach my reporting from a position of stability and power. Rather than competing on a news cycle-centric pitching treadmill, I invest resources in complex longform, longterm investigations, run via my own platform, currently hosted at Medium.com: INSURGE intelligence.

Over the last three years, I’ve broken exclusive investigations on national security, surveillance, foreign policy, and the environment, which would never be commissioned anywhere. Yet many have gone viral and led to mainstream media pick-up all over the world.

Writing from the margins can impact the news cycle. But it’s difficult to produce deep, complex stories within the constraints of that cycle. Editorial pressures, business pressures, ideological pressures converge to squeeze out complexity and nuance.

And often, the best stories take years to develop. My exclusive two-part series on how Google was seed-funded by the CIA and NSA is the longest, densest piece I’ve ever written, but it was also the most popular.

The research for the story developed out of multiple threads I’d uncovered in previous reporting on surveillance, the militarisation of social science to augment drone warfare, and the Pentagon’s disturbing ‘Skynet’-style artificial intelligence plans. There’s a need for patience in watching how these threads evolve and intersect. Patience that traditional media institutions don’t have, and increasingly can’t afford, which is why they’re investing less and less in investigative journalism.

So writing from the margins has been empowering. Simultaneously, the crowdfund has given me the bandwidth to make sure my mainstream columns at VICE and Middle East Eye focus on under-reported issues where other journalists aren’t looking.

But reporting from this intersection between the margins and the mainstream with no institutional support can have unforeseen consequences.

Last summer, I was threatened by a law firm in Turkey, closely connected to President Erdogan. The firm wanted me to delete my exclusive story on covert Turkish military-intelligence sponsorship of jihadist groups in Syria, including the ‘Islamic State’ (ISIS).

This investigation raised grave questions about the conduct of the ‘war on terror’ in Syria, why the war on ISIS was failing, and the awkward silence of NATO on the behaviour of one of its own leading allies in the region.

As an independent journalist with little institutional support, the prospect of being sued by a foreign firm with links to an authoritarian state was deeply unsettling. I was frankly terrified that should the threat go ahead, it could mean the end of my journalism — or the silencing of not just me, but more importantly, my brave whistleblower source.

I have refused to delete my story.

The second case occurred later in 2016, when I discovered that I’d been unofficially blacklisted by the British government.

Earlier that year, I’d been commissioned by the London-based national hate crime charity Tell Mama UK to investigate the trans-Atlantic network dynamics of the far right. The investigation uncovered alarming evidence that the British Tory government had fostered a range of self-serving connections with neo-Nazi parties in Europe, many of whom were tied to groups that radicalised Thomas Mair, the neo-Nazi coward who murdered Labour MP Jo Cox.

(It also identified the direct connections between the Donald Trump campaign team and neo-Nazi sympathisers in Europe, way before everyone else started talking about it,).

Then in July, Tell Mama UK was threatened by a senior Home Office counter-extremism official for commissioning my investigation. Sabine Khan of the Home Office Organisation for Security and Counter Terrorism’s Research Information and Communications Unit (RICU) told Tell Mama UK’s chairman that senior Home Office officials were deeply troubled by the charity’s association with me — a critic of the UK government’s counter-extremism programme, Prevent (for failing to prevent real extremism while self-defeatingly criminalising dissent). If Tell Mama continued to work with me, the official warned, the Home Office would pressure the Department for Communities and Local Government to pull funding from the charity.

I filed an official complaint with the Home Office to which, in breach of their own protocol, they failed to respond.

That sort of experience brings home to me again and again the importance of making independent journalism sustainable. Radical journalism needs to be free to challenge power, not just in terms of financial autonomy from vested interests, but also in terms of the institutional power to resist backhanded methods of state censorship.

Crowdfunding doesn’t solve this problem, but it does mean, at least, that a journalist is able to draw on members of the public to support investigative work that otherwise would never get published.

It also means that I’m not alone. The work of an investigative journalist can be lonely, even if working as part of a newspaper. But having a crowd around you to draw on when you require support changes the game.

I get insights and feedback from my supporters, and they have direct access to me. What I’ve learned from this is that the crowd, the community, are more than just a financial resource. They are an immense intelligence resource; providing new leads, new ideas; pointing out holes and nitpicking over details; requesting new stories, and suggesting new avenues of inquiry.

And they are also travelling companions. The crowd, the community, participates in your journey, and often takes the opportunity to light the way forward. They learn from you and you, in turn, learn from them.

But the design of both journalism and crowdfunding platforms is massively ill-equipped to facilitate this sort of generative dialogue. Not only is it difficult to keep track of conversations, the very design is not conducive to having them. And, of course, these platforms have no mechanisms to generate new journalism on the basis of these conversations.

The other limitation is that unless you strategically invest in marketing, the growth potential is limited. Altogether, over the last two years I’ve singlehandedly raised a total of nearly $70,000, with barely any advertising (I’ve invested around a few tens of dollars in occasional Facebook ads), purely through the strength and appeal of my journalism.

I’m proud of this achievement, but I’m also conscious that I couldn’t have done it without having had a mainstream profile, through which I’d already built up a significant following. And I’m also conscious, by the same token, that crowdfunded journalism is not in itself a signifier of journalistic integrity.

Just look at Ezra Levant’s therebel.media, an arch example of a crowdfunded platform which hosts anti-Semites and proto-Nazis. The crowd is not always right.

The key is in the design. Is it possible to design a platform, a social network, which brings people from diverse perspectives together in a way that cultivates not extreme polarisation, but generative dialogue?

It has to be. Because if we don’t repair our ability to communicate with each other in a way that’s conducive to collective learning, we face escalating global crisis.

Life and death

Fallen

As a species, we now find ourselves at a pivotal fork in the road. We can either continue business-as-usual, which entails an accelerating path toward escalating mass extinctions, unprecedented environmental destruction, and a virtually uninhabitable planet — or we can bootstrap into our coming post-carbon future by adapting and evolving through a systemic transformation that brings us into harmony with our environment, and ourselves.

We face a civilisational choice of momentous proportions. We either choose life, or we choose death.

And yet, as a species, we are cognitively impaired. The dissarray of our global media institutions, the ‘fake news’ crisis, the accelerating polarisation in our media and political discourses has produced a bizarre state of ‘information overload’.

Our collective consciousness as a species is mired in extreme fragmentation, dislocation and confusion. As a result, we not only find ourselves retreating more and more into our isolated bubbles of social media discourse; we are finding it difficult to communicate with those who disagree with us; and as a whole, we have become increasingly disempowered from being able to coordinate meaningful systemic action in response.

The crisis in journalism is a symptom of this wider civilisational crisis. It exists because information in this system has become, largely, an acceptable weapon of psychological warfare, deployed by multiple, competing centres of power, to maximise material accumulation for the few in the form of profits from advertising revenues; and by extension to influence our behaviours in the form of what we buy, watch, eat, drink, wear; often through the casual manipulation of our beliefs and values.

This is not a conspiracy. It is the day-to-day, perfectly normal and, within its own structural context quite rational operation of governments, corporations, businesses, nonprofits and numerous other actors.

Each of us finds ourselves drowning within this sea of competing information everyday. The experience of an acceleration of information overload is real.

As I discovered in my new scientific monograph, Failing States, Collapsing Systems: BioPhysical Triggers of Political Violence, information overload is a symptom of what happens during a ‘phase-shift’ from one systemic configuration to another.

Evolutionary biology teaches us that organisms under environmental stress must be able to accurately process information from their environmental context through the process of genetic modification. Only then can they undergo the systemic biological adaptations necessary to evolve and survive.

The complex adaptive system of human civilisation now encounters a parallel threshold. The heightened sense of global ‘information overload’, and the accompanying experience of disempowerment, disillusionment, and paralysis, represent a civilisation in the midst of a ‘phase shift’. We can either scale this process toward a new, adaptive system that actually works. Or we can regress into a series of deepening crises.

So the stakes could not be higher. We need an approach to journalism whose fundamental goal is to establish a framework, an information architecture, by which we can collectively truly understand the systemic complexity of our predicament; and thus collectively coordinate actions in response which build the basis for a new system.

We need simplicity in complexity; and unity in diversity; we need constructive conversations where disagreement and contradiction form the healthy foundations of generative dialogue that produces new insights; we need productive ways of networking which augment meaningful social relationships based on these insights which coordinate real-world change.

And we need this right now.

Madness

Ego

Because right now, journalism and journalists are under threat. Which means our collective cognitive impairment as a species is breaking apart, precisely at the historic juncture when we need it most.

Over the last two and a half decades, 60% of US journalism jobs have vanished. Similar trends are visible in the UK and Europe.

The decline in the number of journalists has particularly impacted local reporting and investigative journalism, which requires longer lead times, more research and specialist knowledge or experience.

As journalists are dying out, they are being replaced by a new breed of journalistically-trained PR specialists, many of whom have learned the hard way that a career in journalism is financially unsustainable.

The shift toward PR is part of a wider trend in which corporate advertisers and special interests dominate global information highways.

Amidst the digitisation of media, the emergence of technology companies as de facto publishing and distribution platforms which control their own advertising streams has seen them take an increasing slice of the financial lifeblood of traditional media.

Despite massive increases in advertising spending, fully 65% of digital ad revenue is controlled by just five giant technology firms, Google, Facebook, Yahoo, Microsoft and Twitter.

This has also raised new questions about the editorial power of these firms over what their users read and watch, compounding an already tightening editorial noose inside the media.

In the US, six huge transnational conglomerates own and control the entirety of the mass media, including newspapers, magazines, publishers, TV networks, cable channels, Hollywood studios, music labels and popular websites: Time Warner, Walt Disney, Viacom, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp., CBS Corporation and NBC Universal.

Today, the world’s largest media owner is Google, followed by Walt Disney, Comcast, 21st Century Fox and the CBS Corporation.

These corporations control the bulk of what we read, watch and hear, including online. They define our understanding of the world and even ourselves.

But they represent the world’s most powerful elites. The directors and shareholders of these media conglomerates interlock with each other.

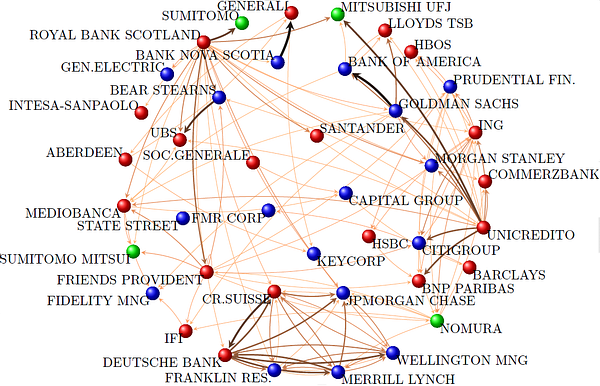

They form part of what one study in the journal PLoS One describes as a “network of global corporate control.”

Examining the ties between 43,000 transnational corporations, the study by a team of systems theorists at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology found that they are dominated by a core of 1,318 companies.

These companies represent dominant control over the world’s productive resources: Wall Street, Big Pharma, Big Oil, Agribusiness, Silicon Valley, and the Military Industrial Complex.

In turn, the web of ownership behind these core power-brokers track back to what the study described as a “super-entity” of 147 firms.

This is the nexus of power that underpins the existing global media architecture — an architecture that is not only increasingly unable to comprehend and process the very information it absorbs; but which is fragmenting and miring itself in escalating incoherence.

While the editorial noose is tightening as this global media-industrial complex attempts to squeeze the last drops of profit out of mass consumption of information, newspaper circulation is still declining, along with total advertising revenue among publicly traded media companies — across both print and digital.

The chronic ad dependency creates a vicious cycle in which consumers seek to extract whatever value they can, while producers simply generate more content pliable to the interests of advertisers. Instead of producing more revenue, this process is eroding the intrinstic value of content produced, distancing the relationship between producers and consumers, and generating higher volumes of lower quality content. Meanwhile, revenues for journalism outlets continues to decline.

What’s happening to journalism is afflicting media more generally. Viacom, which owns MTV, Comedy Central, Nickleodeon and Paramount, faces a consistent decline in profits. Walt Disney Co.’s profits are falling. So are Time Inc.’s. And News Corp’s. Etc.

Journalists are feeling the results on the ground. We are becoming cogs in a dying machine.

Many journalists find themselves on a news cycle treadmill — whether due to editorial pressures in the newsroom, or the financial pressures of being a freelancer — producing or processing anywhere between 10 and 20 news items a week. As a result, the culture of journalism has eroded from one that rigorously investigates and challenges power to merely furnishing factoids and regurgitating opinions.

In the UK, twice as many journalists believe that their freedom to make editorial decisions has decreased over time as believe it has increased. A large majority also believe that time for researching stories has decreased while profit-making pressures, PR activity, and advertising considerations have all strengthened.

These large, bureaucratic centralised structures of media production and dissemination are being disrupted by new social technologies which give increasing power to consumers and smaller producers in a more decentralised landscape.

Disinformation masquerading as ‘news’ can be widely distributed for mass consumption at relatively little cost.

The digitisation of advertising revenue has incentivised this outcome, by making clickbait potentially highly profitable for micro-platforms that keep their overheads as low as possible, while dishing out ‘search engine optimised’ stories designed to game Google.

Simultaneously, faced with this onslaught of fake news competitors, traditional media institutions find themselves struggling to compete, and to retain the attention of their desired audiences.

This is translating into two fundamental challenges. Firstly, unlike the new fake news outlets, traditional media has overheads. Big overheads. But increasingly, traditional media is discovering that in the age of digital everything, advertising revenues are insufficient to fund worldwide reporting for the 24/7 news cycle.

Secondly, the rapid growth in fake news demonstrates the reality of rapidly growing popular unease with traditional media. There are now mass audiences all over the world, hungry for information outside the traditional global media circuit. It is those mass audiences that have enabled the proliferation and popularity of ‘alternative’ news sources on both the left and right of the political spectrum.

For the most part, those alternative news sources suffer from their own limitations. They are either very well-funded by interests tied clearly to specific political and ideological agendas — think Breitbart News or Russia Today; or they lack a level of resources even remotely comparable to the traditional media institutions with which they are competing.

Yet there is a giant elephant in the room: the fact that the crisis of fake news began inside traditional media. In fact, the most egregious cases of fake news have been promulgated by traditional media institutions.

And it is precisely the mass disillusionment and breakdown of trust with traditional media institutions that has been the biggest driver of all.

News consumers are fed up with being lied to — they no longer have trust in the ability of prevailing media institutions to tell the truth.

Lies

This stark reality was recently set out in a written submission on fake news to a UK Parliamentary Inquiry, by a group of academic specialists on media and propaganda, Prof. Vian Bakir (Bangor University), Prof. David Miller (University of Bath), Prof. Piers Robinson (University of Sheffield), Prof. Chris Simpson (American University, Washington DC).

The document identifies the real problem — the systematic promulgation of fake news by traditional media institutions in the form of government or corporate propaganda:

“Over a century of fake news: Today’s furore over fake news must be seen against the backdrop of over a century of systematic political and commercial efforts in liberal democracies such as the UK and USA to persuade and influence populations through mass communication. From scholarly tomes to ‘how-to’ manuals, a large body of knowledge has emerged concerning the histories and techniques of propaganda, PR, public diplomacy, political marketing, strategic communications, strategic narratives and spin. Similarly, military circles have generated practices of perception management, psychological operations, information operations and public affairs.”

So what exactly was happening over this ‘century of fake news’ which traditional media institutions managed to misconstrue?

This: a horrifying continuum of violence wrought by Western military interventions across the less developed world since 1945 until today, violence that played a critical role in the process we obliquely refer to as ‘globalisation’.

The number of people that died in the course of these interventions in over 70 developing nations across Asia, Africa, South America and the Middle East is astonishing.

In his book, Unpeople: Britain’s Secret Human Rights Abuses (2004), British historian Mark Curtis offers a detailed breakdown of the death toll from these largely US and British-led interventions. Curtis builds up his picture not from media reports, but from declassified official documents.

The total number of direct and indirect deaths from these US-UK military interventions is approximately 8.6–13.5 million — a conservative underestimate, he qualifies.

This grotesque continuum of violence was never properly investigated or acknowledged by most of the press when it was actually happening. And it remains largely unknown to most journalists and editors today. Nor is it given much attention in the academy.

Our cognitive institutions do not acknowledge or comprehend its existence.

As Curtis also shows, this violence was often systematically obscured in the press, with blame being placed on the Soviet Union, or Communists. Today, declassified government documents reveal the reality: usually these Western interventions were motivated to crush nationalist, independence movements, with ‘Communism’ frequently exaggerated as a mechanism of justification.

Since then, press complicity in the abuse of power — whether by acquiescing in propaganda or selectively ommitting important facts — has become even more entrenched and complicated.

The parliamentary submission sets out some key examples.

One is deception through outright lying: In 2004, the authors note, the George W. Bush administration “paid actors to produce news, journalists to write propaganda, and Republican party members to pose as journalists.”

Then we have deception through distortion: By early 2005, the way the British press reported the scale and imminence of the post-9/11 terrorist threat, quoting anonymous intelligence sources, became so frequent that media articles were even being used by government ministers to justify policies: the authors point out that the British security services themselves became concerned by the abuse and politicisation of this journalism.

We also have deception through omission: The British government’s infamous ‘dodgy dossier’ of 24 September 2002, which set out official claims about Iraq’s Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD), was not based on intelligence ‘errors’, but rather “deceptively portrayed a misleading picture of greater weapons capability and greater certainty than the intelligence warranted.” Most of the press slavishly put forward this deception as if it was fact, with very little questioning.

Another main category is deception through misdirection: In 2014, the Obama administration declassified the Executive Summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee report on the Bush-era CIA Detention and Interrogation Program. This scapegoated the CIA, but made “no demands for responsibility to be taken by the Bush administration that secretly ordered the Program; or by its lawyers that secretly legalised the Program to avoid CIA operatives from retrospectively being charged with torture.” This approach impacted the way the press reported the issue and demanded accountability.

It also concealed the fact that the Obama administration had effectively rehabilitated the torture regime, as I reported here.

The outrage over fake news is understandable.

But it is being used rather cynically as a stick to beat everyone else with, while making sure to avoid looking in the mirror.

The problem is always ‘out there’. Never ‘in here’. And thus ‘fake news’ becomes the card of convenience to be rolled out and used to point at anything we disagree with, whether we are ‘left’, ‘liberal’, ‘right’, ‘conservative’, or whatever.

The fake news crisis really just means this: traditional media institutions once held a monopoly on the information highways.

This monopoly was systematically abused in service to various special interests, generating numerous instances of deception and propaganda.

As that monopoly is breaking down, the mainstream is finding itself disrupted by smaller, digital-only outfits allied with a wide array of different interest groups, including many who are still tied to various special interests.

In particular, what we’re seeing with the rise of entities like Breitbart, for instance, is how the digital space has opened up possibilities for cross-sections of power within Wall Street, Big Oil, and so on, to pool resources and challenge the mainstream monopoly.

Yet the design of their journalism is reactionary, polarised, and self-interested to a degree that undermines its integrity.

What we have here is the acceleration in the breakdown of our collective tools of cognition as a species. Our information sensors, the mechanisms by which we make sense of and act in the world, are in intensifying disarray.

Now we have multiple centres of news which are, in a way, simultaneously fake and non-fake: all of them producing their own narratives, often highly polarised, in a way that leaves the average person with little choice except to cherry-pick their way through the mass of information trying to piece together a semblance of coherence.

This is a global crisis of information: and it’s a symptom of the Crisis of Civilisation. It’s escalating precisely as we scale the current ‘phase-shift’ into what could either be a series of systemic breakdowns, or a sequence of systemic adaptations.

No algorithm, social media authenticity measure, or subscription revenue model add-on, will alone solve this problem, because it’s mere tinkering with a declining system.

We don’t just need a new outward model of journalism, with different structures here and there.

Journalism needs a radically new mode of orientation. One that returns to its essence — speaking truth to power, to transform power.

And the new mode of orientation will be aligned with a very different way of existence in the world, a new set of structures that cultivate this approach, a shift from having to being, from endless extraction to mutuality.

That is why I am building a new media ecosystem. Because, as a species, we really have no other option if we want to adapt, evolve, and thrive.